The Back Room is pleased to present Symphony No. 1 : Symbolic Compositions, the first solo exhibition in Malaysia by Brazilian artist Kika Goldstein. Comprising 20 paintings, a painting installation, and 20 sound pieces composed in response to the works, the exhibition draws on prehistoric cave art, layered abstraction, and spiritual cosmologies to build an immersive, multi-sensory experience.

Based in Kuala Lumpur since 2022, Goldstein has been steadily developing a unique body of work informed by field research, symbolism, and the resonance of ancient forms. Her practice, which she calls an “archaeology of memory” investigates the layers through which shapes, colours, stories, and symbols accumulate, whether through dreams, family archives, or ancestral landscapes. Her works extend beyond their surfaces, often incorporating natural materials like natural pigments and soil, and now sound, to create environments that invite observation, contemplation and sensorial perception.

Born in São Paulo in 1984, Goldstein studied visual arts at Faculdade Santa Marcelina before embarking on a multidisciplinary journey through painting, installation, video, and performance. Her work has been exhibited internationally in Brazil, Germany, China, and Malaysia, and is held in institutional collections such as the Museum of the City of São Paulo and the Regional Museum of Olinda in Pernambuco.

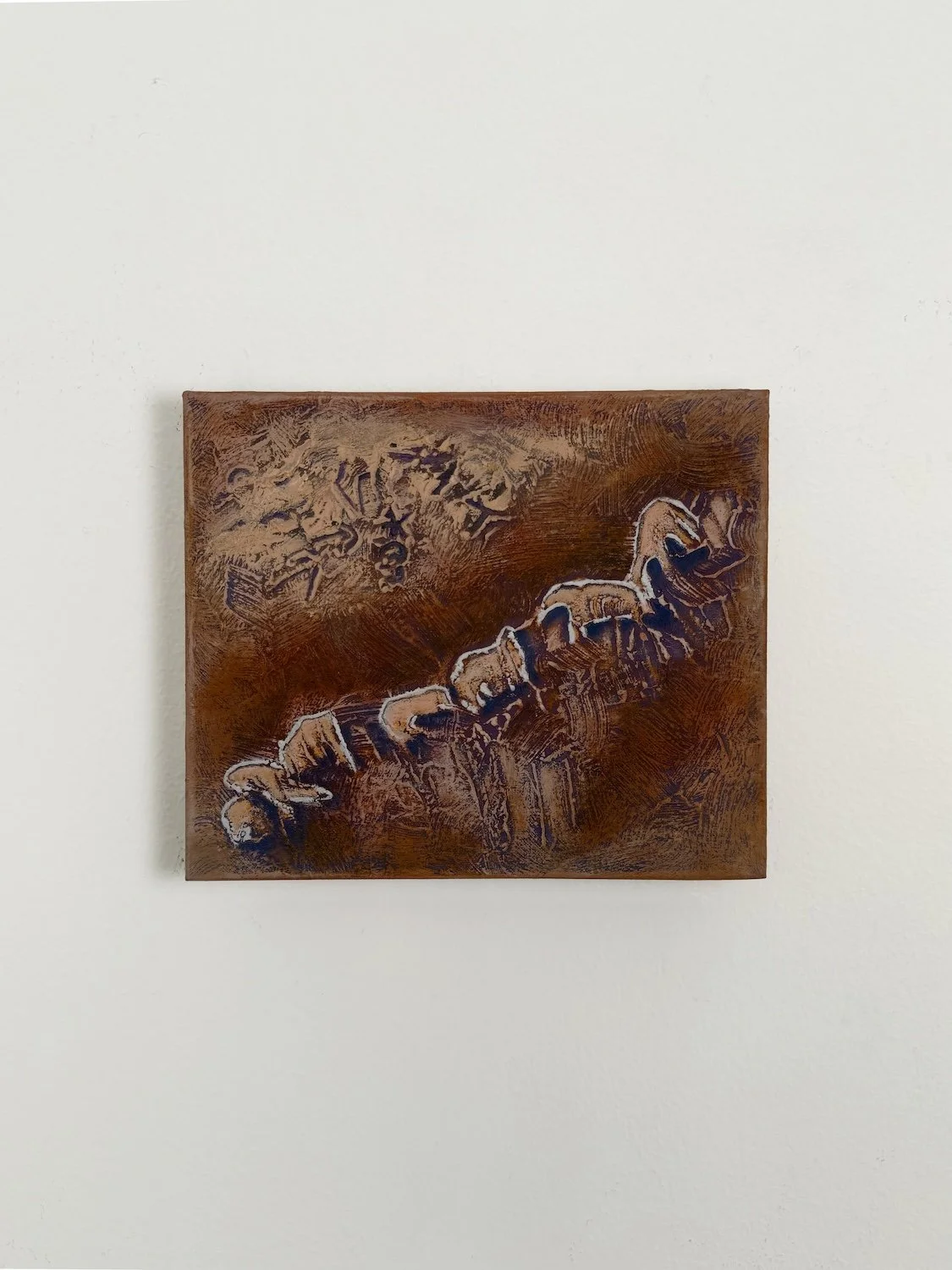

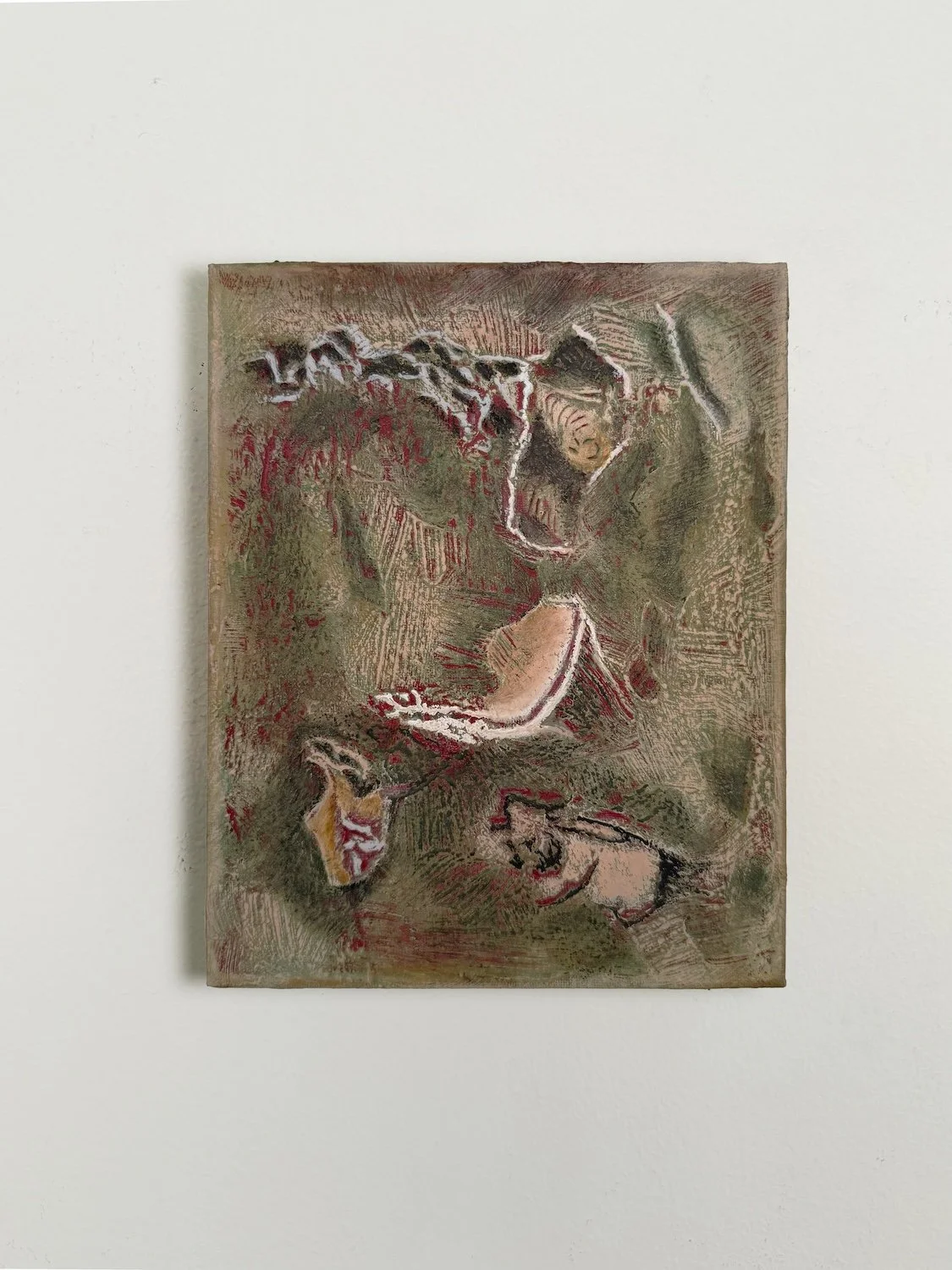

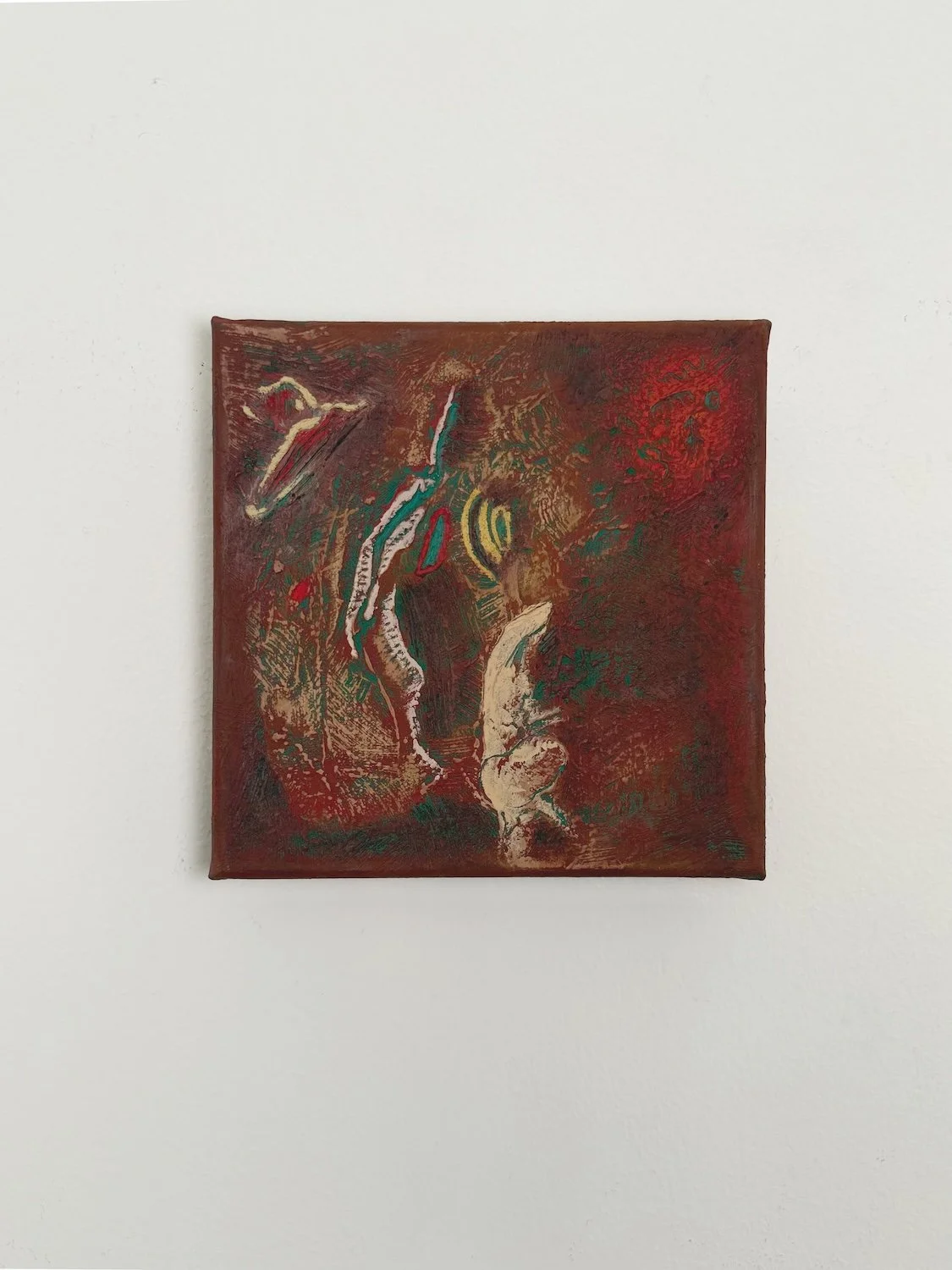

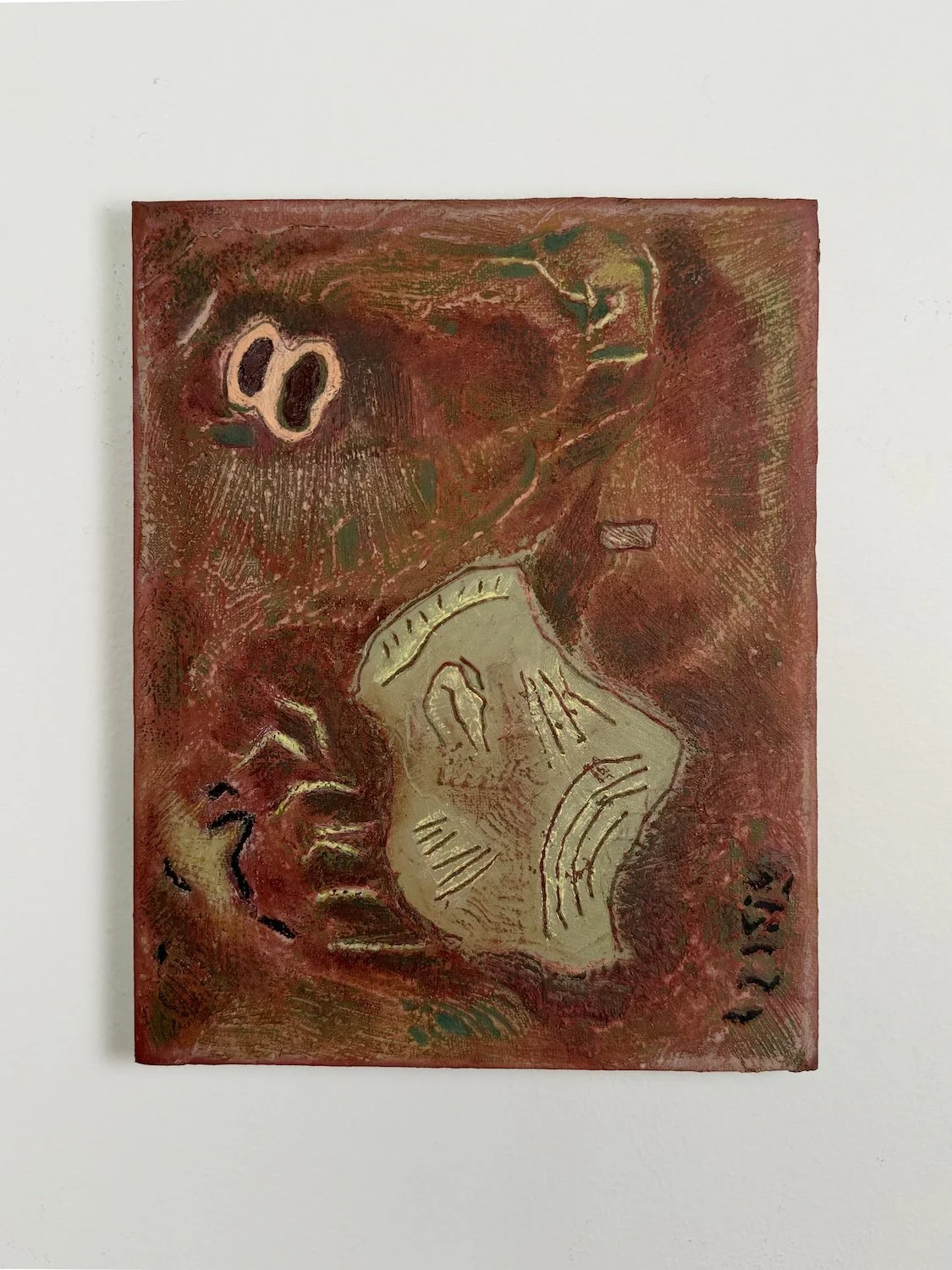

In Symphony No. 1, subtitled Symbolic Compositions, Goldstein turns to the prehistoric caves of Parque Nacional do Peruaçú in Brazil as well as those in Chauvet, France, as sites of sacred expression and early visual communication. Her palette of terracotta, pinks, off-whites, greenish hues, and browns recalls the mineral colours of rock and earth, and her heavily worked surfaces suggest both geological stratification and symbolic inscription. The forms that emerge, crevices, figures, and proto-marks, seem to hover between past and future, reality and dream.

Earlier this year, the artist met with Indigenous women weavers in Sabah and Sarawak as part of her ongoing engagement with traditional knowledge systems. This encounter offered a meaningful point of resonance with her Malaysian context, especially in relation to the storytelling and symbolism found in both weaving and cave painting. In her recent iconography, Goldstein invokes a visual language that is at once symbolic, spiritual, and grounded in nature.

This exhibition positions Goldstein in a broader artistic lineage that includes modernists such as Paul Klee, who was moved by the economy and directness of prehistoric art, and Wassily Kandinsky, whose paintings were deeply musical in intent. With Symphony No. 1: Symbolic Compositions, she continues this legacy: 20 sound compositions accompany the paintings as variations on a single central score. Like the gradual shaping of a new word, or the murmur of a shared memory, these pieces, created by Brazilian musician André Abujamra, parallel the unfolding of a visual language: sensory, mysterious, magical, and alive.

Curated by Flavia Gomes, a curator based between Brazil and Shanghai, Symphony No. 1: Symbolic Compositions is a meditation on the timelessness of image-making — a return to the origins of human expression, and a step toward new visual grammars that transcend oral language. The opening of the exhibition will be accompanied by a talk with the artist and curator on 26 July 2025 (Saturday), 3pm, at Malaysia Design Archive, 84B The Zhongshan Building (same building as the gallery).

About the Artist

Kika Goldstein (b. 1984, São Paulo; based in Kuala Lumpur) is a visual artist whose practice centres on painting as a means to investigate what she calls an “archaeology of memory”, a process in which shapes, colours, images, fragments, and echoes accumulate over time. Her work is driven by the tensions that emerge from the interplay between natural surroundings and old imagery, whether found in books, family photographs, or dreams.

Her compositions evoke imaginary places and scenes that challenge conventional perceptions of time, space, and narrative. Her paintings often transcend two-dimensional limits, projecting themselves into the observer’s space. Recent works have expanded into three-dimensional elements—such as soil, rocks, and large-scale paintings—as well as video and performance, reflecting her ongoing exploration of language and visual expression.

Goldstein has been investigating prehistoric cave art alongside traditional knowledge systems, particularly the craftsmanship of bamboo and rattan basketry. Drawn to their abstract, symbol-laden patterns, she has begun integrating contemporary painting with traditional artisanship to establish a cross-cultural visual dialogue in which symbols function as a form of language. She is also currently developing Weaving Memories, a film project about female, indigenous weavers in Malaysian Borneo.

The artist holds a bachelor's degree in Visual Arts from Faculdade Santa Marcelina in São Paulo. Goldstein’s works are part of prominent institutional collections, including the Museum of the City of São Paulo and the Regional Museum of Olinda, Pernambuco. Her most recent solo exhibitions include Sussurros Simbólicos [Symbolic Whispers] (2024, ArteFASAM Gallery, São Paulo, Brazil) and Opacidade das paisagens [Opacity of Landscapes] (2022, ArteFASAM Gallery, Belo Horizonte, Brazil). She has participated in group exhibitions in Malaysia and internationally, including Annihilation (2023, SNAP Contemporary Art Centre, Shanghai, China), Interwoven Realities (2024, Harta Space, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), Brasilianische Künstler (Galerie D’art Lucia Hinz, Germany), and Art Open (Eschweiler, Germany).

About the Curator

Flavia Gomes (b. 1976 São Paulo, Brazil) is a curator, writer, and researcher based between Shanghai and around Brazil. Gomes’s curatorial practice engages with symbolic language, cosmological thought, and contemporary art, establishing dialogues between traditional knowledge systems and current visual languages. Her research bridges South American and Asian cosmogonies and archetypal expressions, activating connections between mythic narratives and experimental artistic practices.

She holds an MA from the Royal College of Art in London, where her research focused on the surrealist sculptor Maria Martins, culminating in the essay “The Wild Thought of Maria Martins”. In Brazil, she, together with Matias Mesquita, co-founded Elefante Centro Cultural in Brasília, a pivotal independent art space that helped reshape the city’s visual arts landscape. There, she developed exhibition programs, international artist residencies, publications, an arts prize, and public initiatives that expanded engagement between artists and local communities. Gomes is active in supporting independent spaces and collaborative networks, working closely through counsel, writing, and long-term artistic partnerships with emerging and established artists across Brazil, China, the UK, and Malaysia.

Recent curatorial projects include Pulso a Gravidade [I Pulse Gravity] (2025, Galeria 506, Porto Alegre), a collateral group exhibition of the Mercosul Biennial; Algumas Coisas são Vistas Apenas no Escuro [Some Things Are Only Seen in the Dark] (2025, Galeria OMA, São Paulo); Sussurros Simbólicos [Symbolic Whispers] (2024, ArteFASAM, São Paulo); and Annihilation (2023, SNAP, Shanghai). She has participated in residencies in Yunnan, China, with artist Long Pan (2024), and in the Peruaçú National Park in Minas Gerais, Brazil, with artists Anna Paes and Kika Goldstein (2024). In 2025, she co-directed the film Weaving Memories in Borneo, Malaysia, in collaboration with Kika Goldstein and filmmaker Pedro Greene.

Installation shots

Installation images by Kenta Chai.

Exhibition essay

Sound Was the First Thing That Existed

by Flavia Gomes

In January 2023, the artist Kika Goldstein left São Paulo, Brazil, to Kuala Lumpur. The long trip—nearly twenty-four hours including a layover—and the eleven-hour time difference help convey the distance between the two countries. It was a significant geographic shift, and a symbolic one as well: a change that would profoundly affect her life and her artistic production.

Goldstein has an intimate relationship with the landscape. Whenever possible, she would escape into nature: hiking in the Atlantic Forest, climbing mountains, visiting waterfalls, exploring the coastline and national parks in search of colours, forms, and geometric patterns—activities she maintained even after the birth of her daughters. Upon arriving in Malaysia, however, something changed. Despite the exuberance of the equatorial forest—colourful, dense, hot, and humid—the artist turned inward. The sense of strangeness went beyond the geographic distance between her country of origin and her destination: it was also marked by a shift in social and familial routines, which ultimately favoured a process of introspection and solitude that proved essential to her visual work to come.

Goldstein had been engaged in a long-standing investigation in the field of abstraction. Her early paintings, with their small and simple forms, delicate geometric shapes seemingly suspended in space, were defined by her studies on the color wheel and by the presence of the empty space. From free-form studies made with collage on paper emerged a series of paintings whose elements gradually took over the entire surface of the canvas. In these, more complex compositions, Goldstein worked intricate colour schemes and textures that were seen as chromatic territories. The materiality marked by thick brushstrokes and layer upon layer of oil paint mixed with beeswax, creating solid and often opaque colours, amplified the perception that Goldstein’s paintings were becoming increasingly populated. The result was a body of work that nodded toward the tropical Brazilian modernism of Burle Marx and the rational, vibrant chromatic experimentation of Paul Klee.

It didn’t take long before the once-present empty-space began to reclaim its lost space. Goldstein returned it to prominence in subsequent series, and by darkening the colour palette, she heightened the perception of the void, imbuing it with a spatial sensation, as if it were an abyss. Named Nocturnal Landscapes, due to the profusion of chromatic blacks, purples, blues, greens, grays, and browns, with brief zones of light blue and beige that appeared here and there, the landscapes seemed to suggest something new wanting to emerge. Goldstein dedicated herself to making space for the forms that seemed to gently ask to abandon the centre of the canvas to inhabit its margins, requiring viewers to adjust their gaze—just as we adapt our vision to see objects as night falls.

Nocturnal Landscapes was the last series Goldstein produced in Brazil, and the one she returned to upon settling in Malaysia. That was when the dark, opaque, dense, and flat palette—though still maintaining its characteristic texture—softened. Light entered, and with it, what once appeared as an abyss revealed itself as the depth of inner cave chambers.

Naturally, the cave made its way into Goldstein’s painting in her most recent works. When change is profound, we tend to cling to elements that act as bridges to our place of origin, helping us to recognise the new terrain—and for the artist, that place was the cave.

The cave as a mineral element, solid rock, shelter, and place of protection.

The cave as a safe space for family adaptation,

a place to lick wounds and nurture,

a fertile space for reflection, revision, and the gestation of new projects.

The cave as a place of reconnection, correlation, synthesis.

Caves also allude to the origin of painting—to the first gestures that left marks before the creation of images, before the formulation of what makes painting, painting.

I see these two years in Malaysia as a time of great freedom for the artist. Removed from the environment where she had been so well established, Goldstein began circulating in new settings, encountering other landscapes and cosmologies that challenged her worldview and led her to explore new ways of seeing, understanding, and producing art. In this context, she eliminated the borders of the chromatic territories that had previously defined her practice and went further, diving into a body of work with greater investigative density, choosing the empty-space as her starting point, as a space of formulation, and solitude as a necessary place to develop the first murmurings that precede creation.

Visits to the Mulu Caves in Sarawak and an artist residency at the Vale do Peruaçu National Park in Minas Gerais, Brazil, deepened Goldstein’s perceptions of topographic representation through stratigraphic layers, which reveal mineral deposits and materialize the passage of time, since time is a fundamental component in the construction of surface. In Peruaçu, for instance, there is an abundance of limestone cliffs bordered by lakes and slopes, where we can clearly see the colourful lines composing their morphology over thousands of years, as well as patches in various shades of green, pink, yellow, and brown, likely derived from deposited plants, animals, and minerals in a clear indication that time is continuously moving.

These topographic investigations prompted a shift in Goldstein’s treatment of her painting surfaces. She moved away from the formalism of restrained and calculated gestures and began working with solid layers of paint, employing freer gestures and more fluid layers of oil paint, still mixed with beeswax, later overlaid with oil sticks in distinct colours, revealing the underlying light and creating the illusion of a desired material depth. The predominant color scheme developed in the studio draws from mineral species and pigments collected on-site: whites, greens, pinks, yellows, ochres, and browns.

The cave painting appeared almost unexpectedly, still within the context of the artist residency at Vale do Peruaçu National Park. Cracks, holes, fissures, recesses, and reliefs of the caves Goldstein studied led the artist to a rock walls where dots, lines, stains, carvings, scribbles, figures, and markings were not mere topographical or geological accidents but intentional gestures made by beings who inhabited the region at least 25,000 years ago. In the silence of her studio, during the painting process, Goldstein realised that the topography of her works seemed to evoke the figures seen on those walls—and thus a new iconography surfaced, as if through an archaeological excavation. Goldstein preserved the solid pictorial treatment of the figures, as found in Peruaçu, adding lines created by the incision of pointed tools—similar to those used in sgraffito techniques with clay sculpture. These figures, however, are free interpretations of references found in Brazil as well as from other investigations of cave paintings discovered in European and Asian regions—studied by scientists eager to find correlations and meanings that have yet to be determined.

Herons, bison, horses, oxen, cassava roots, a falling man, dots, simple lines. Graphic schemes, arrows, spirals. Symbols that seem more like forgotten codes. A dancer. Silhouettes of mountains that, I believe, are somehow beginning a dialogue with the Asian painting tradition to which Goldstein was exposed during her time in Malaysia. Lizards, another bison. Other dancing figures—or perhaps in ritual trance? A hunting scene. A scene that seems to depict migration.

We look at things with contemporary eyes, always seeking to weave meanings and associations to what we see. But is comprehension necessary for contemplation?

How to name a work born from visual explorations that precede language, where word, image, and sound are indistinguishable?

A close look of Goldstein’s works in her studio, she perceived a vibration, a sort of rhythm unfolding, as if a story was in motion. That was when she invited Brazilian composer André Abujamra, who responded to each painting with a sound. He came up with 28 sound variations of a single matrix, which, when brought together, form a symphony that intensifies the synesthetic experience and magnifies the sacredness of what remains enigmatic.

Sound was the first thing that existed.

Artworks

Each artwork is accompanied by a short sound piece made in response to it by Brazilian composer, André Abujamra.

Variation No. 1

2025

Oil, beeswax, oil pastel, natural pigment on canvas

25 × 30 cm

Listen to accompanying sound piece by André Abujamra