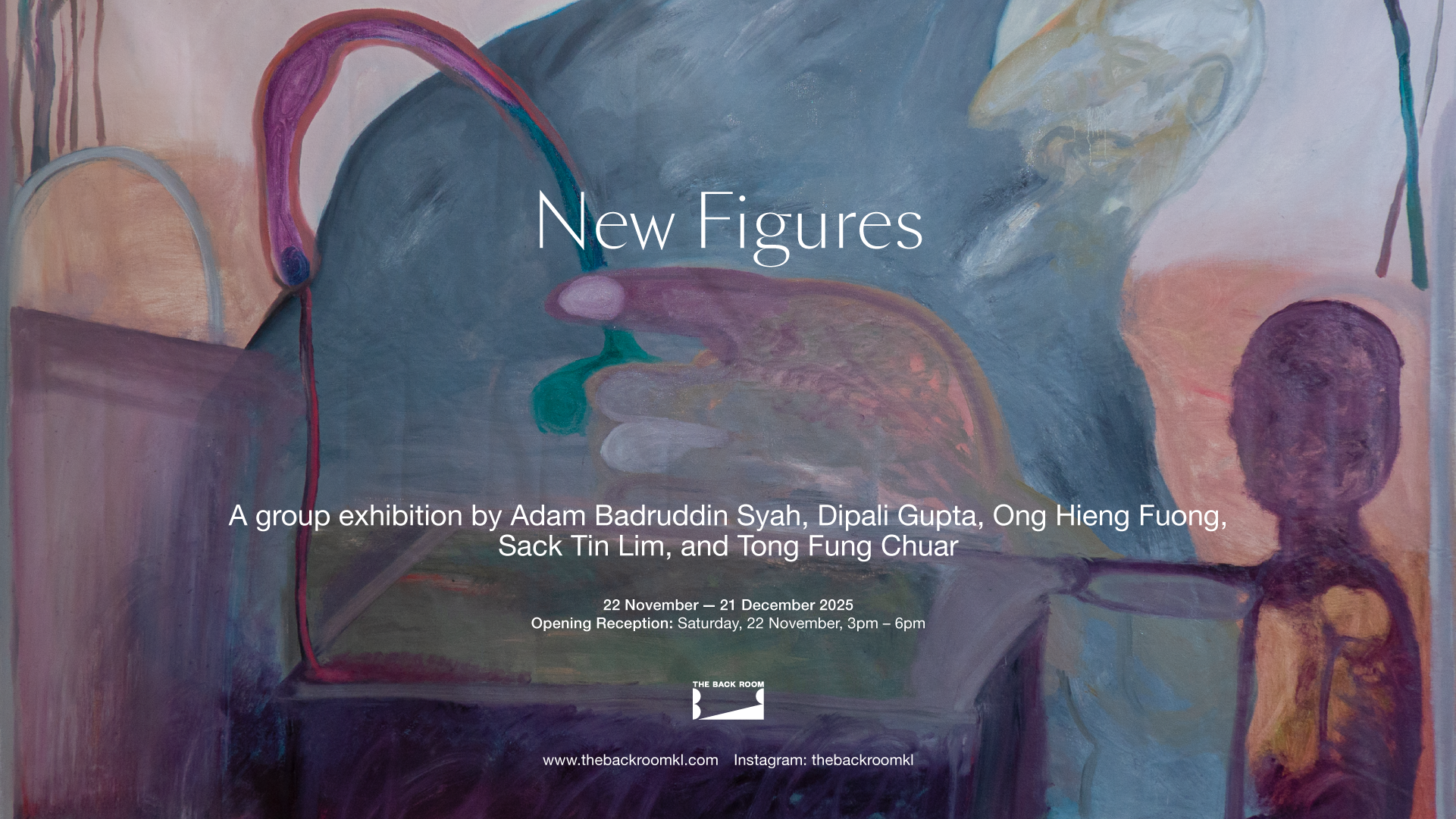

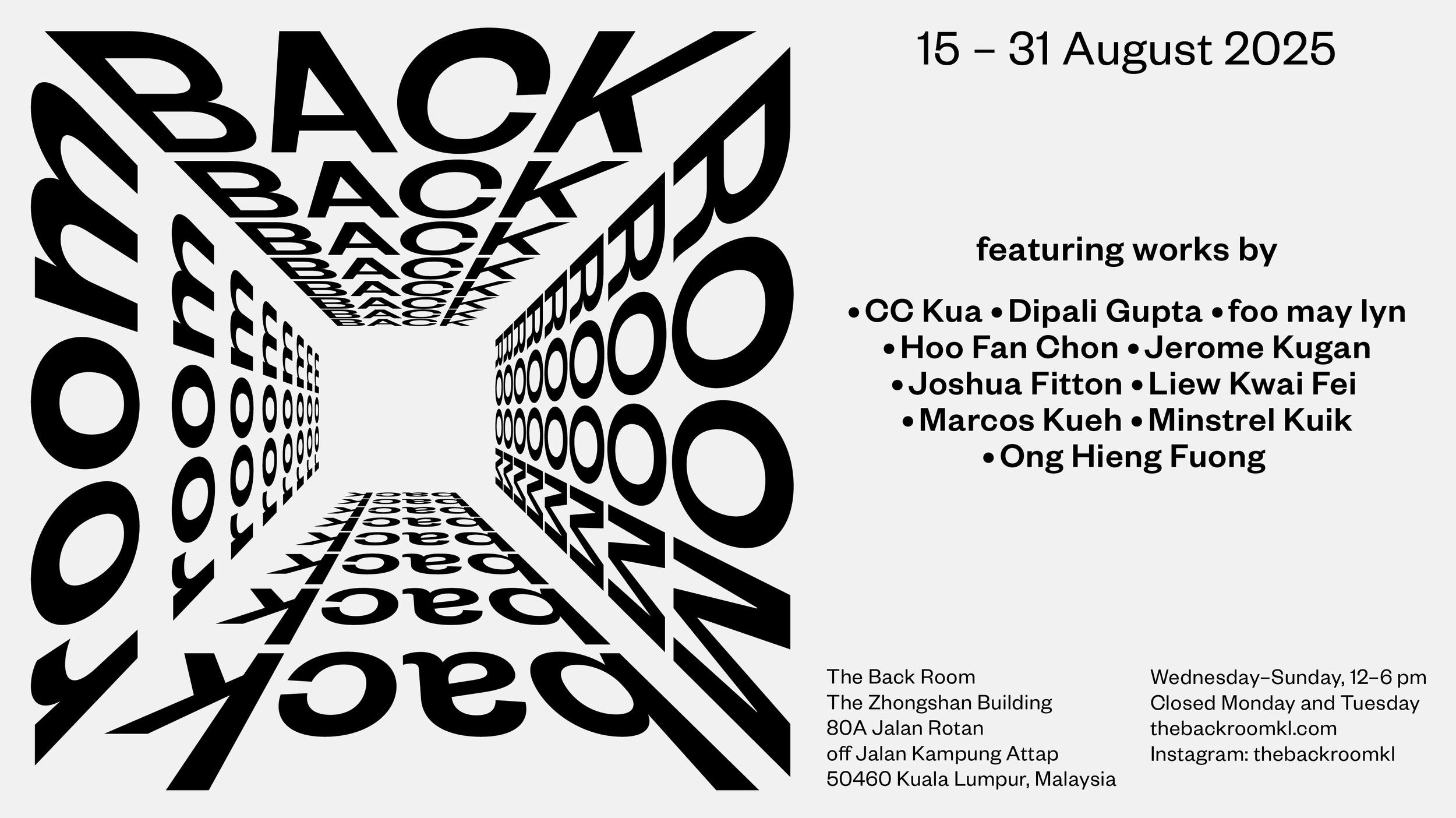

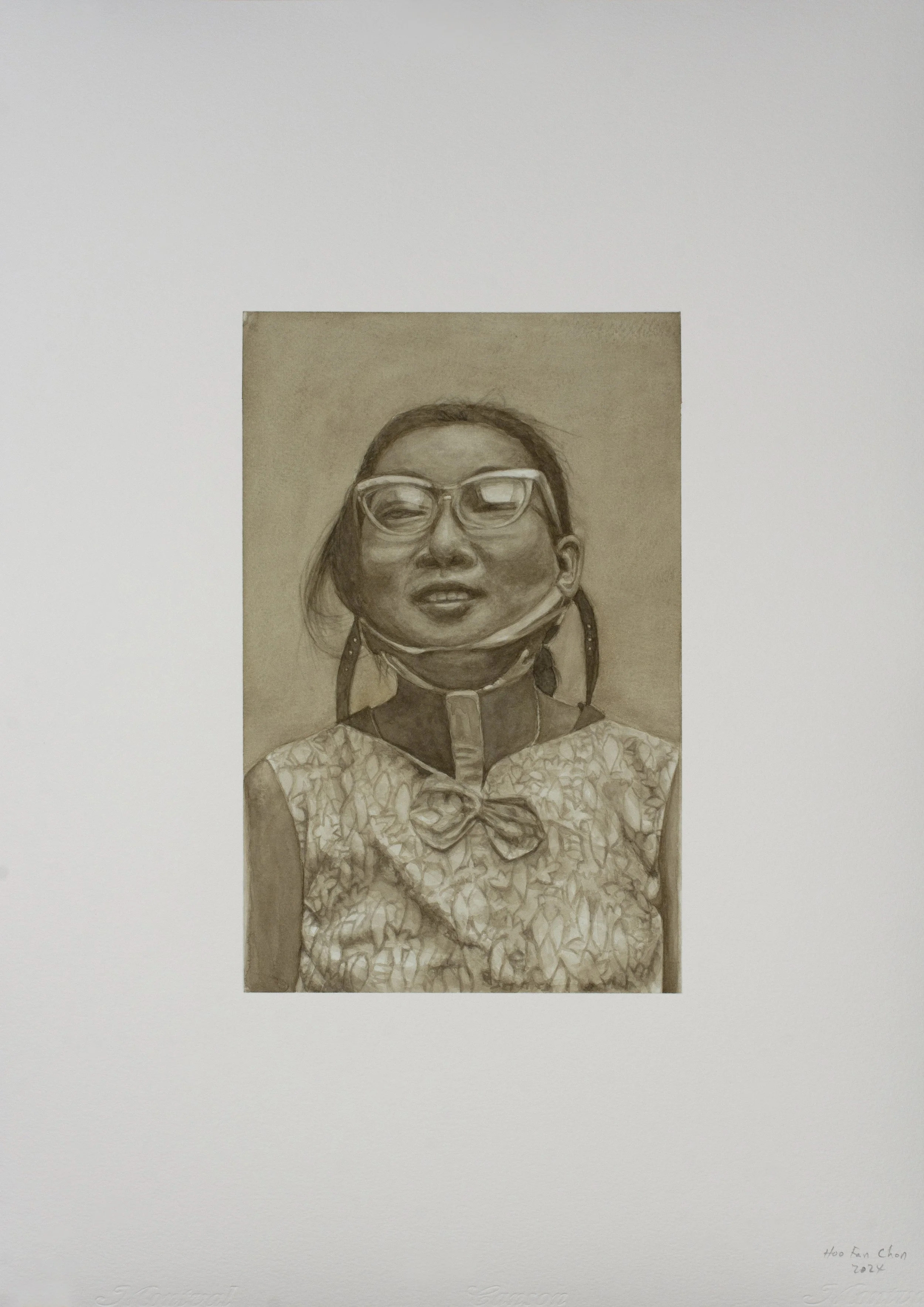

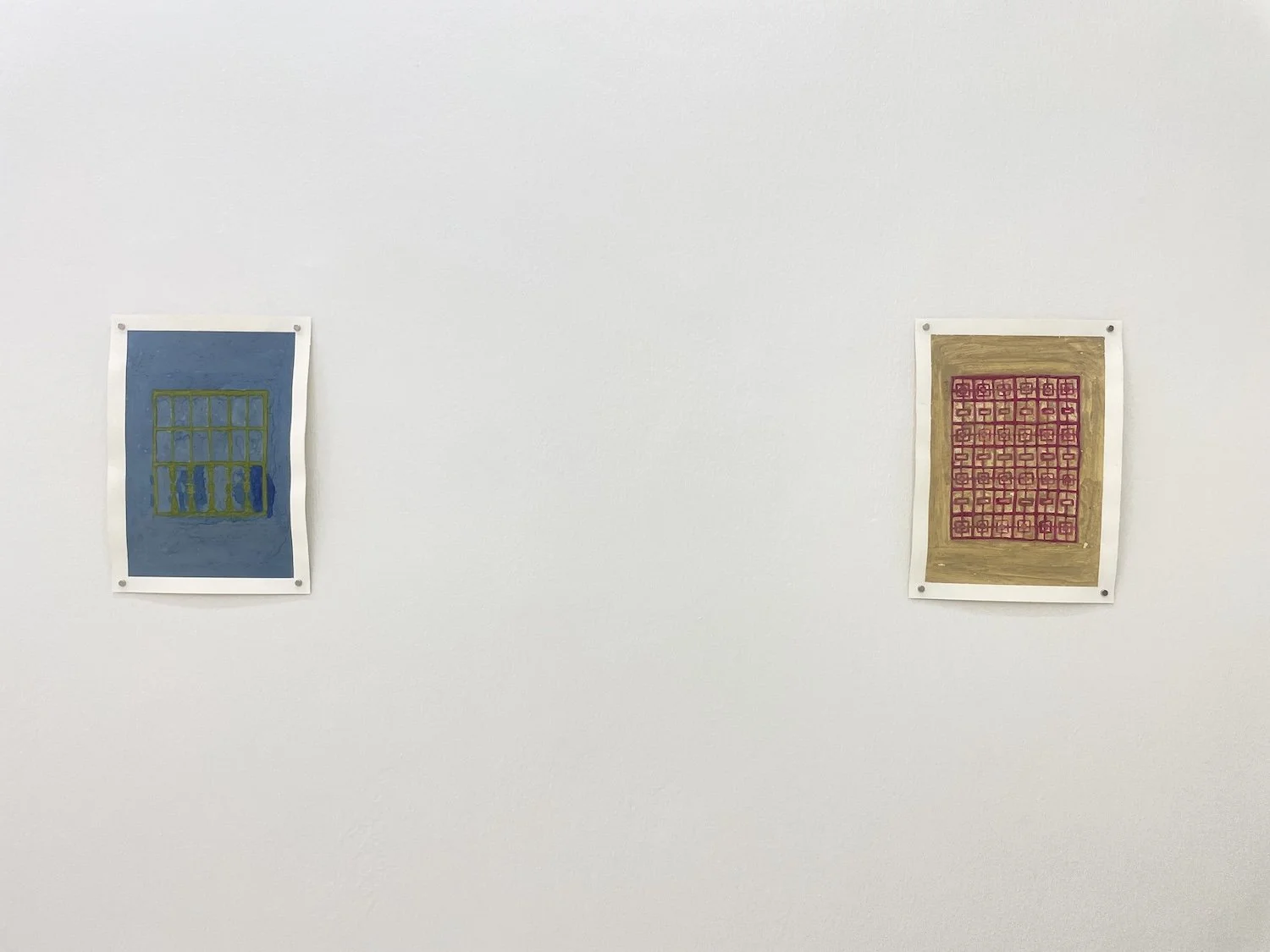

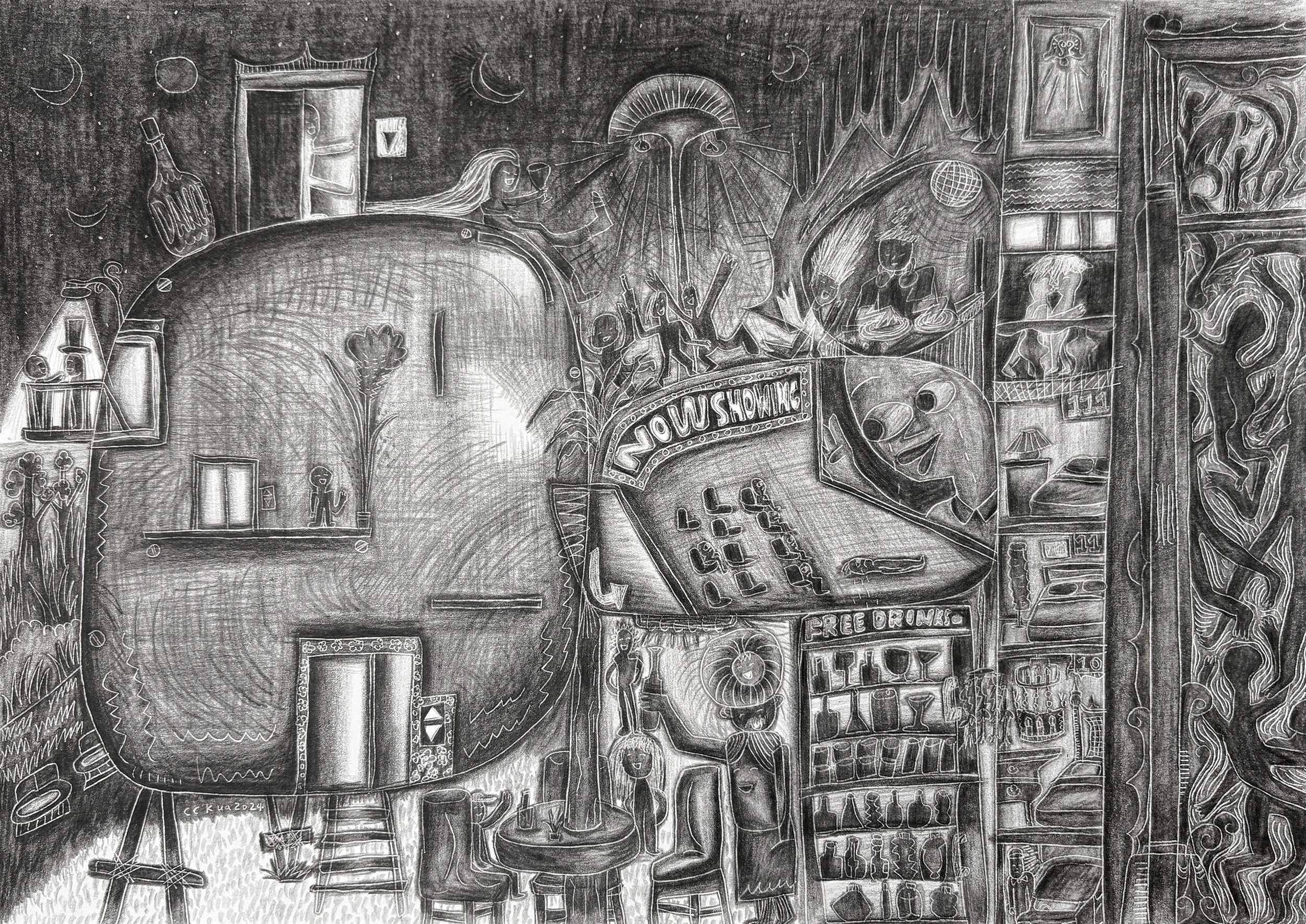

New Figures by Adam Badruddin Syah, Dipali Gupta, Ong Hieng Fuong, Sack Tin Lim, and Tong Fung Chuar

In some ways, figurative painting can be said to be the most revealing genre. The way an artist paints another often reveals how they feel about their own self or about humanity in general. New Figures presents six compelling paintings by five emerging painters, all working in the genre of figurative painting. They use figurative painting, variously, to capture fleeting impressions of the world around them, or the essence of individual lives, or as a meta-commentary on the fluidity of the body.

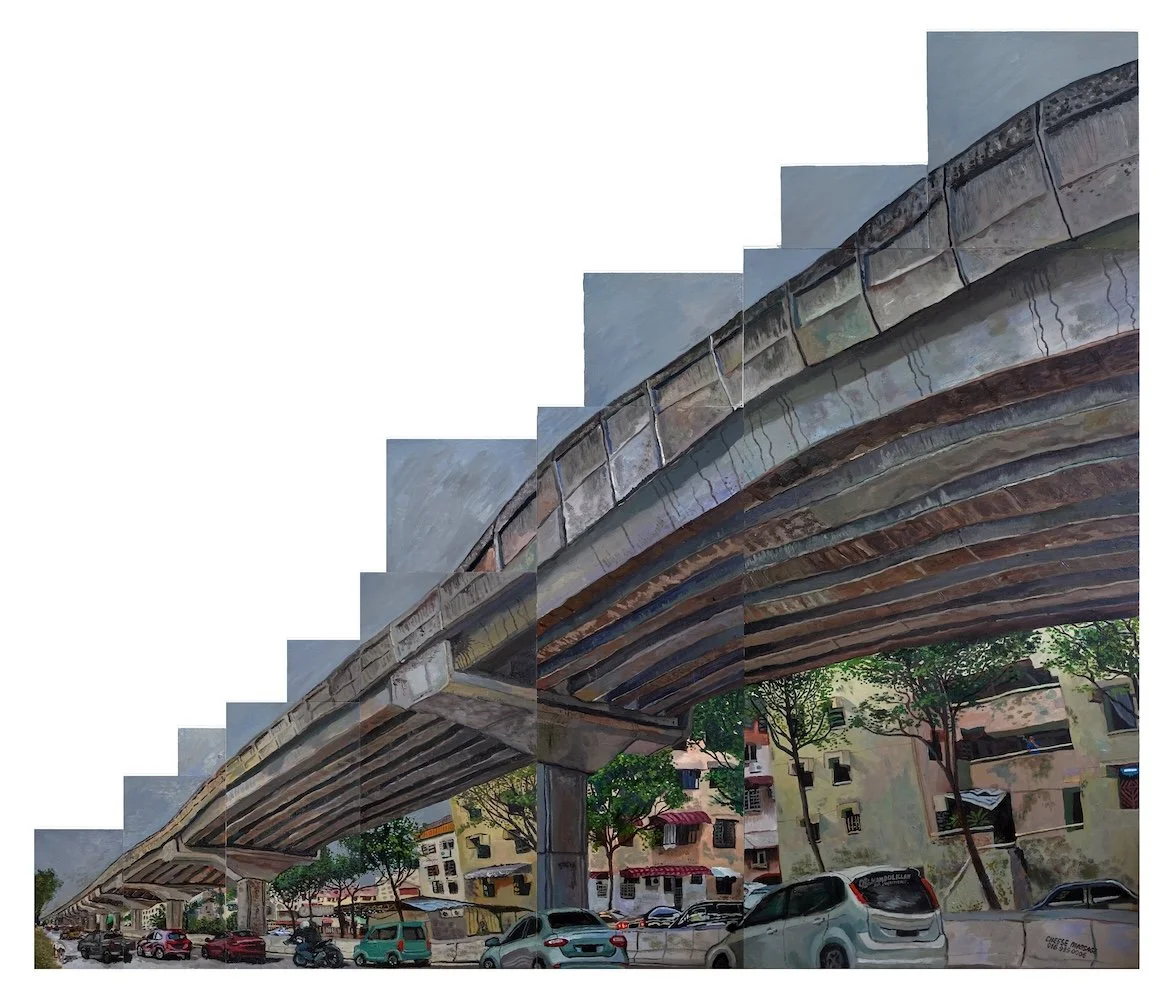

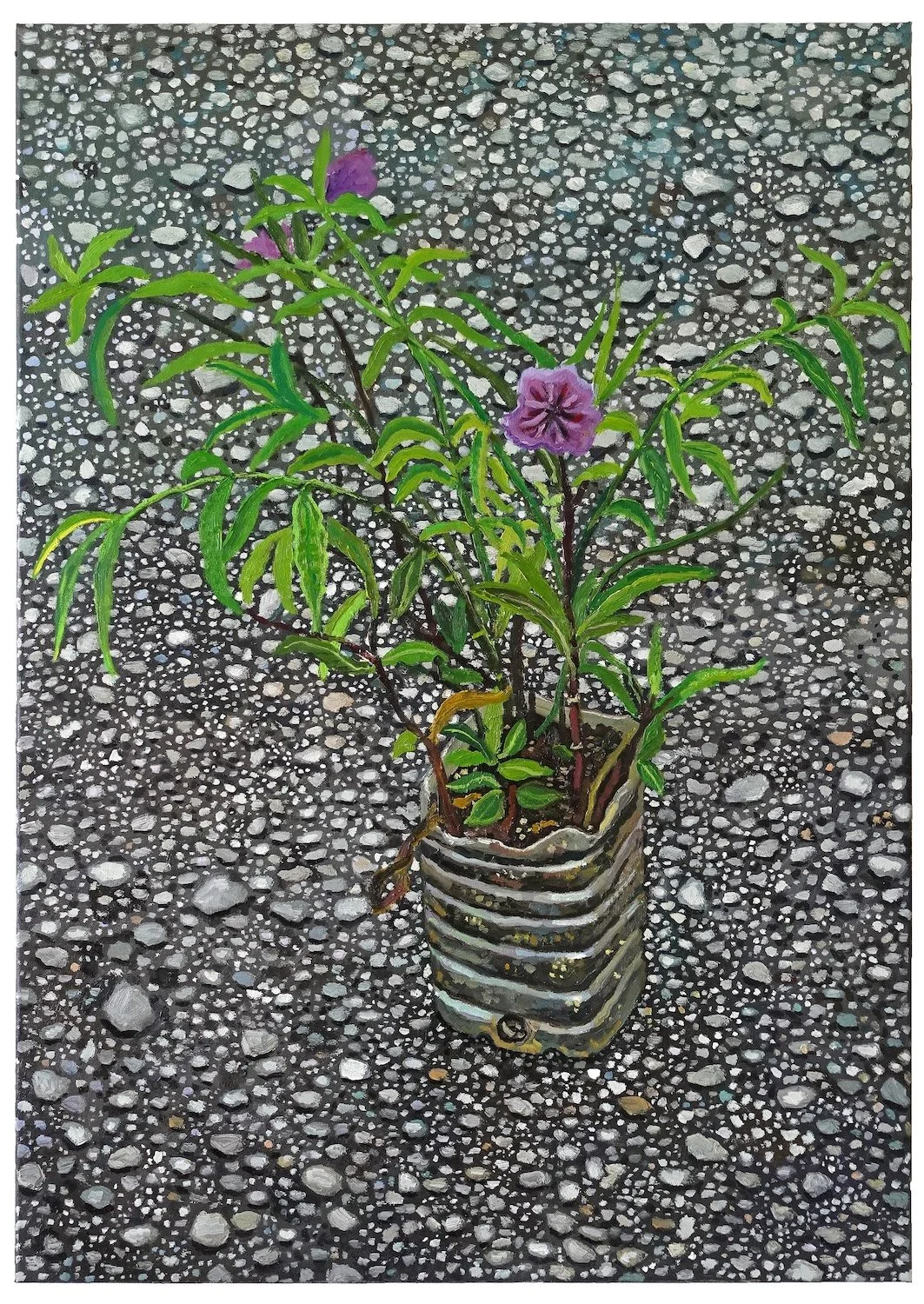

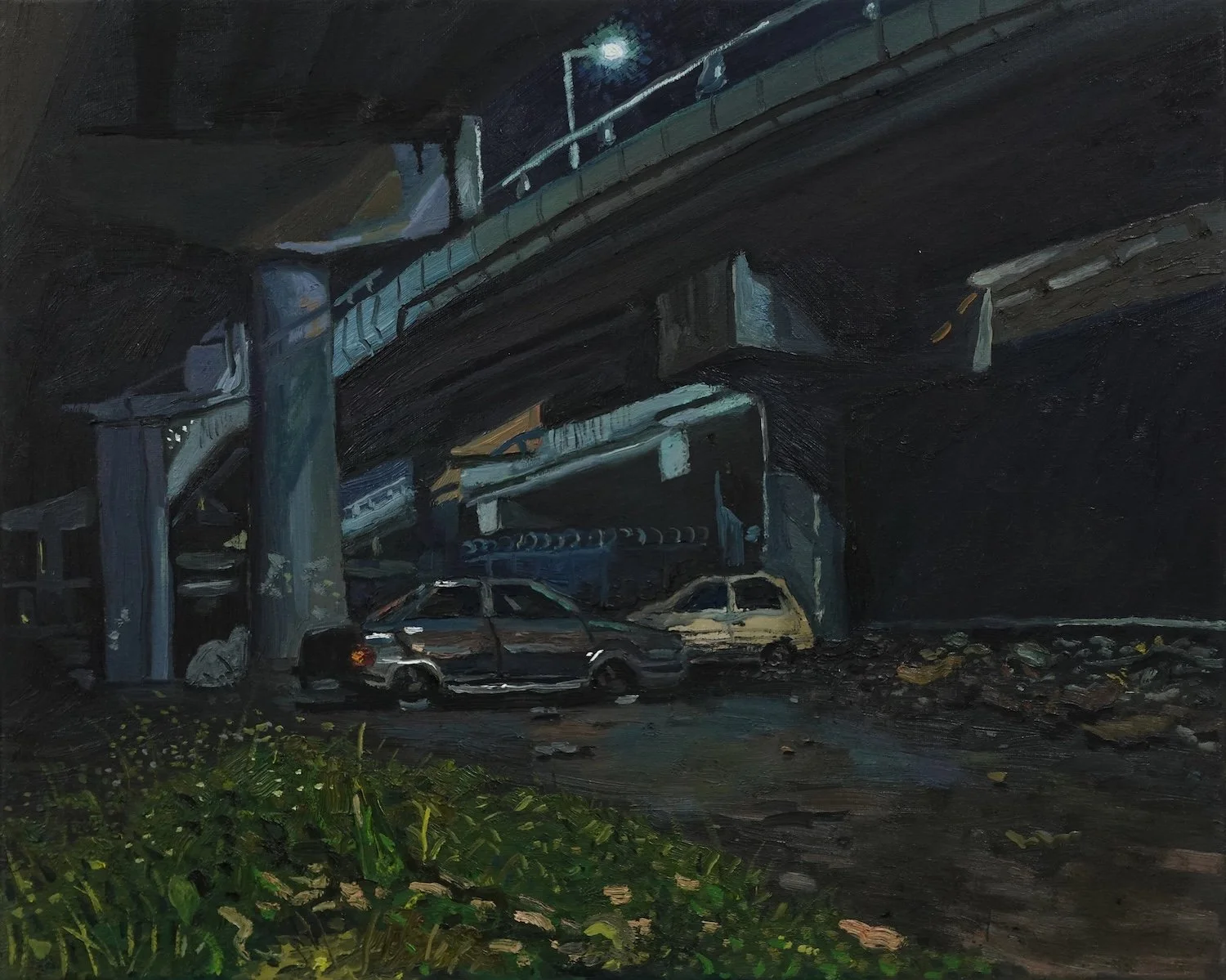

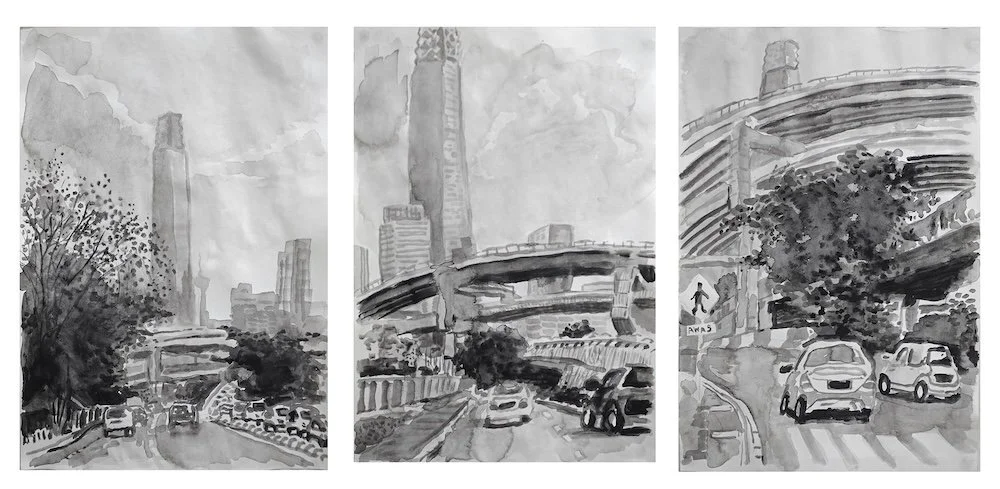

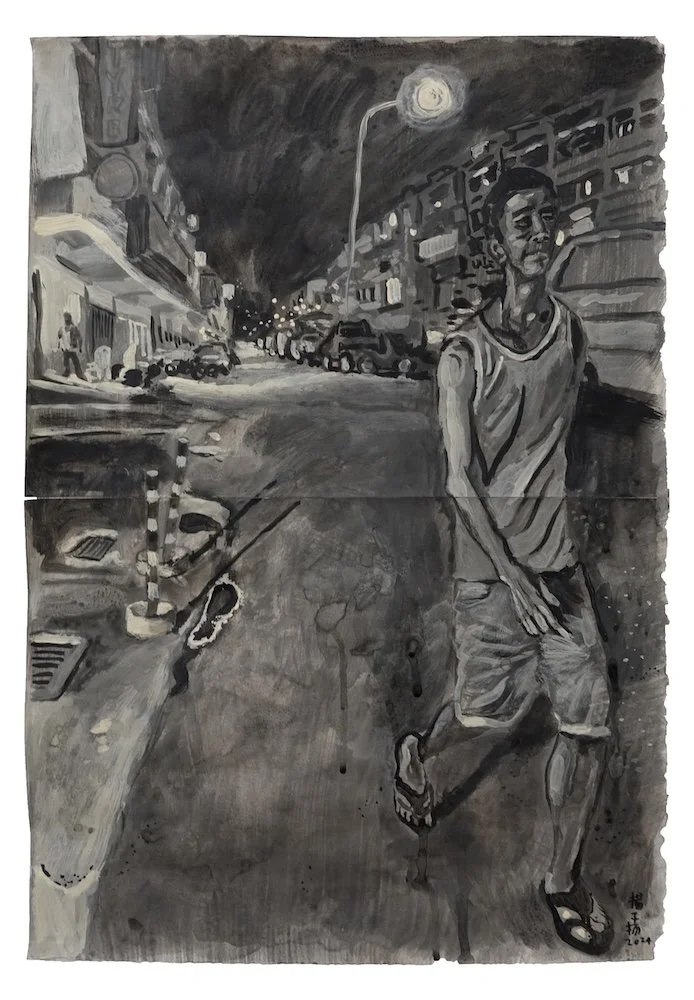

The painting practice of Adam Badruddin Syah is inspired by the late-19th century French Impressionists, but utilises a colour palette more appropriate to the light and shadows of Kuala Lumpur. Layers of colour transform an ordinary mamak into a dense scene inviting lengthier contemplation.

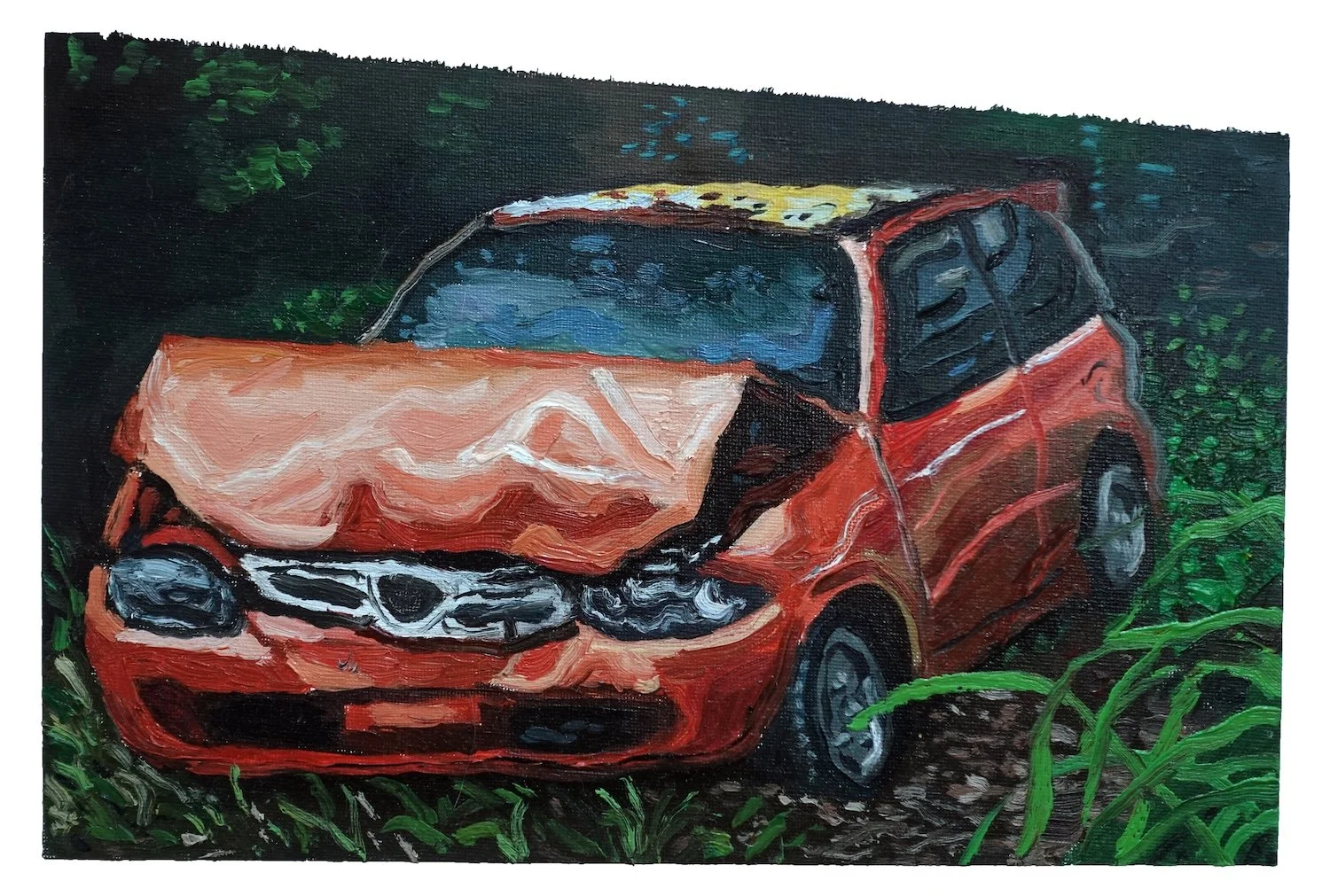

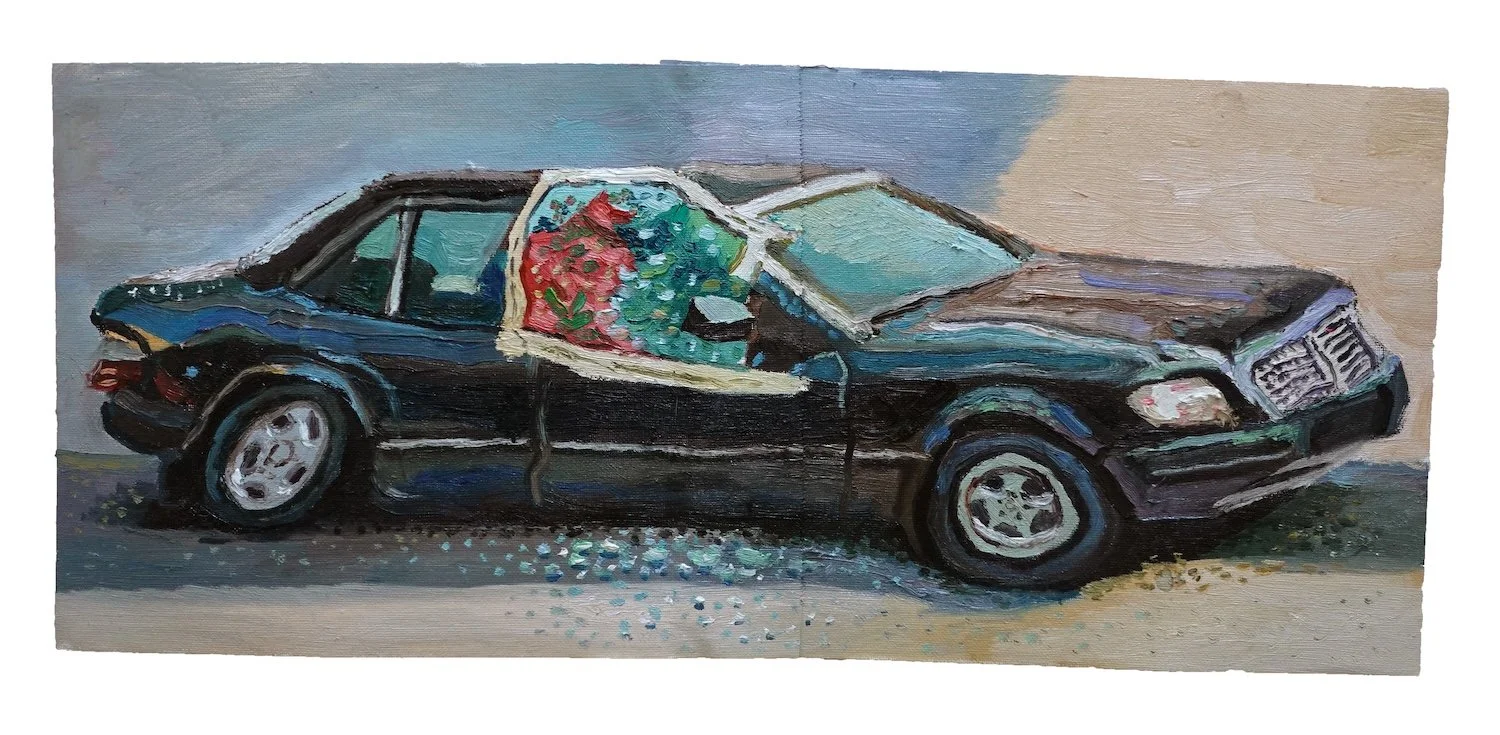

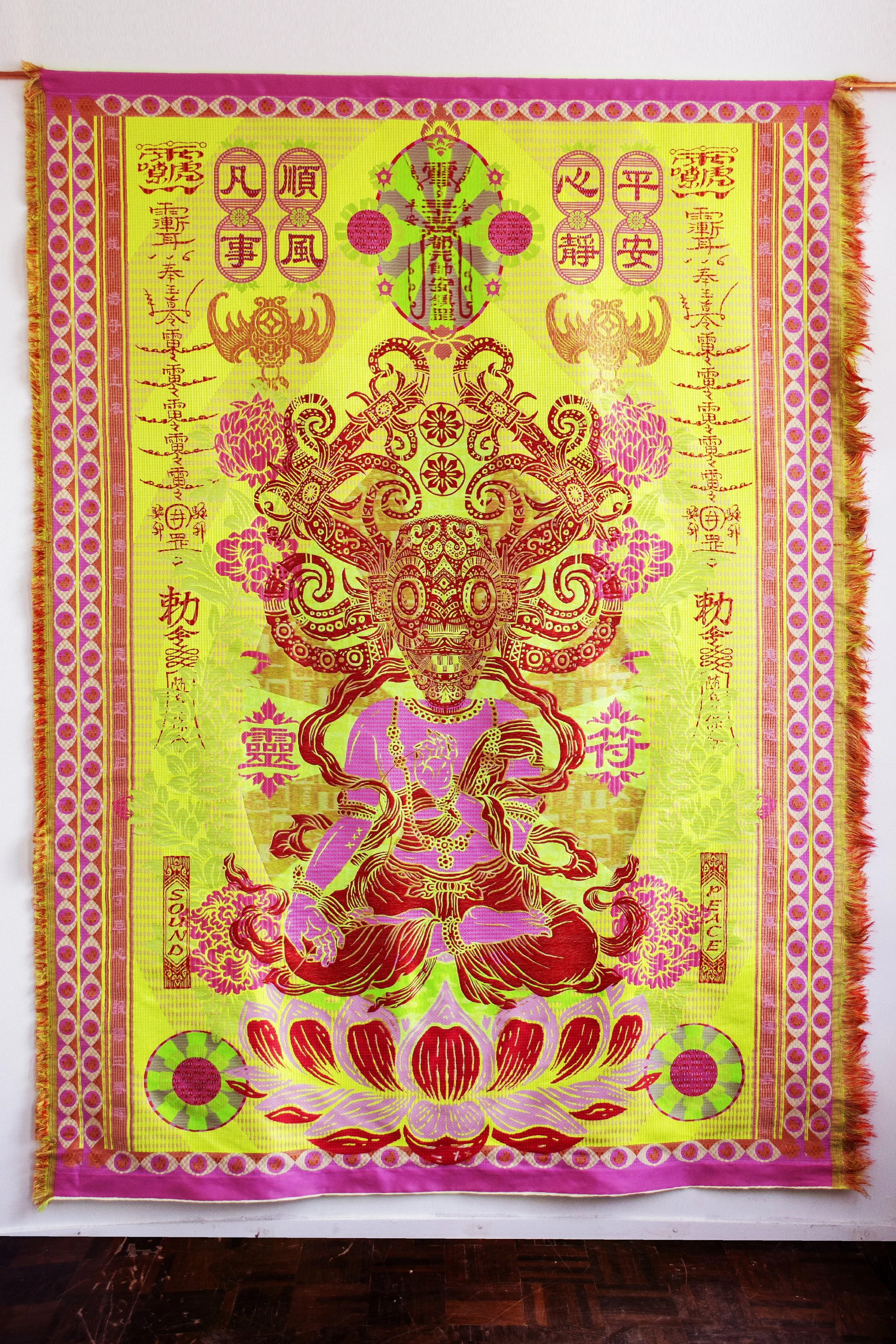

Meanwhile, the figures of Ong Hieng Fuong are painted with a dramatic contrast and saturated colour that makes them seem plastic. In his world, humanity is a rotating cast of cartoon characters, endlessly involved in various comic situations and shenanigans.

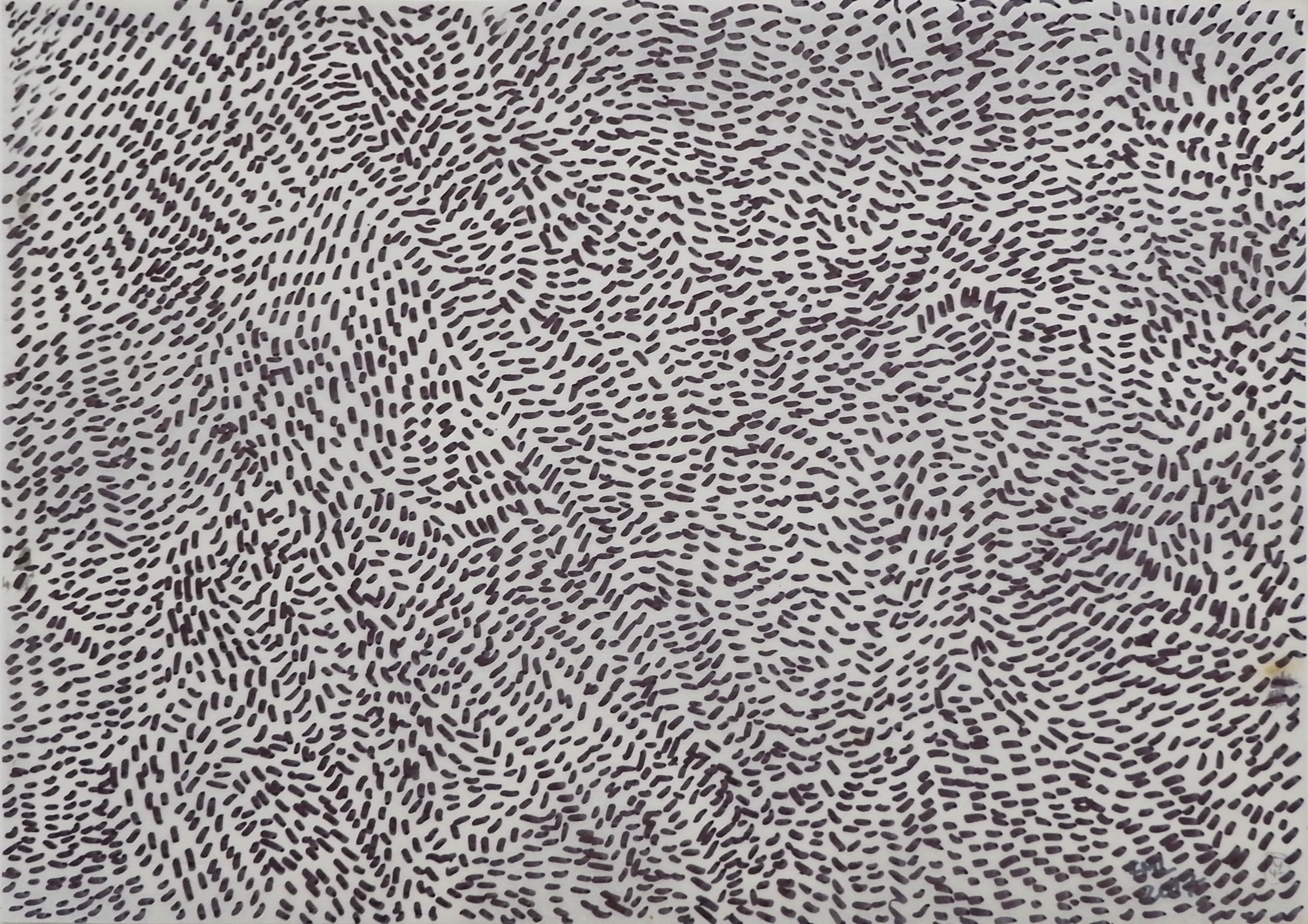

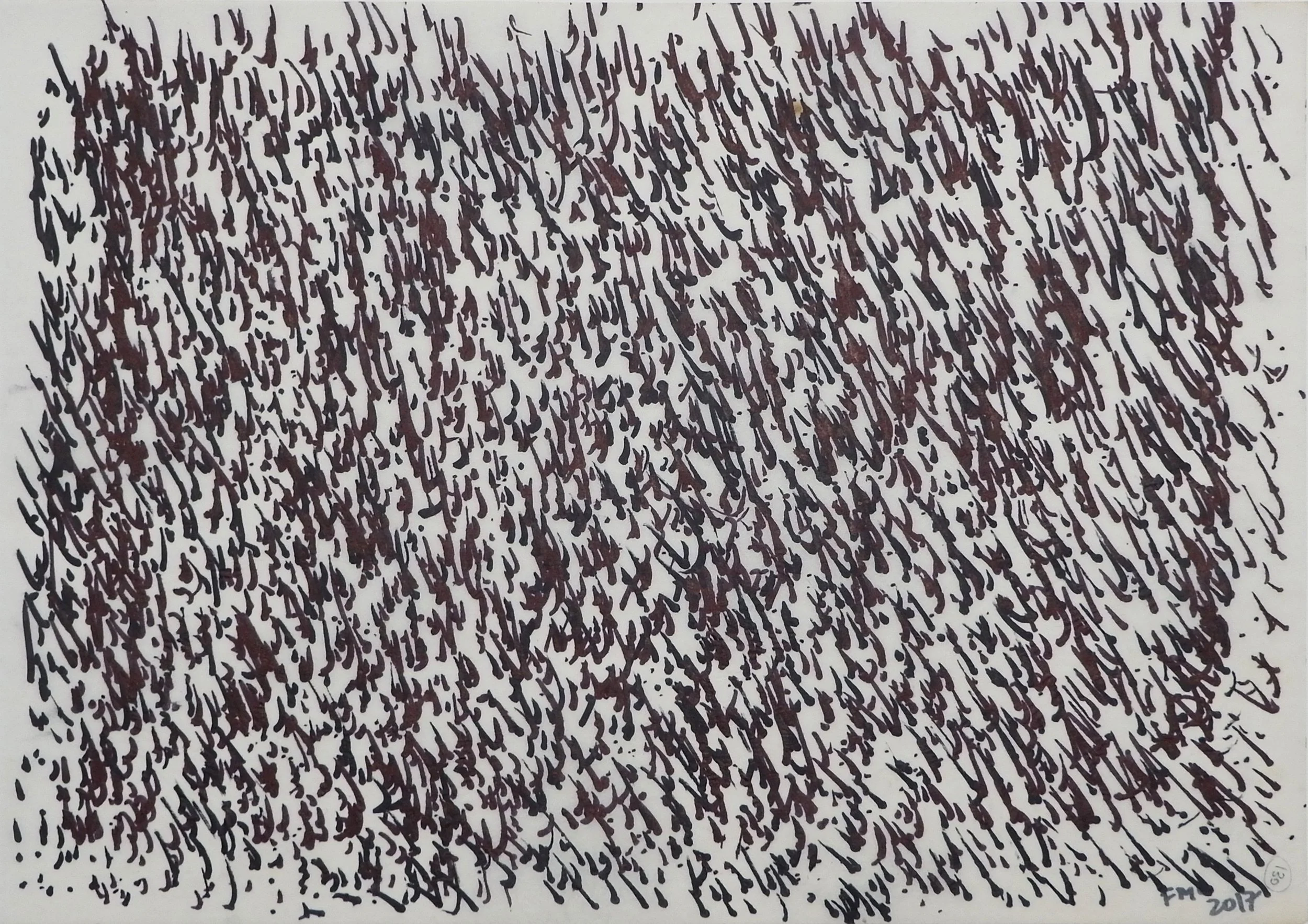

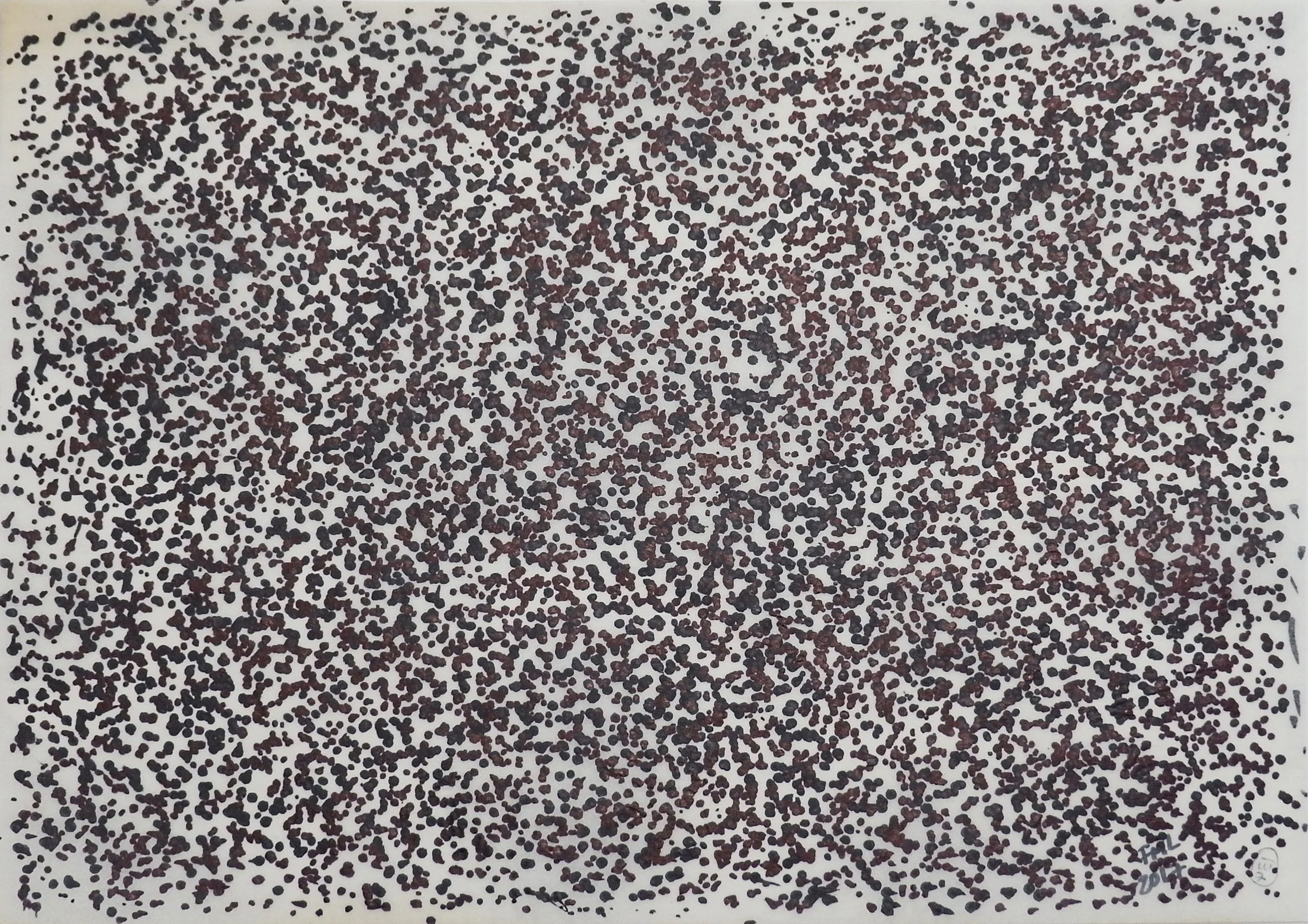

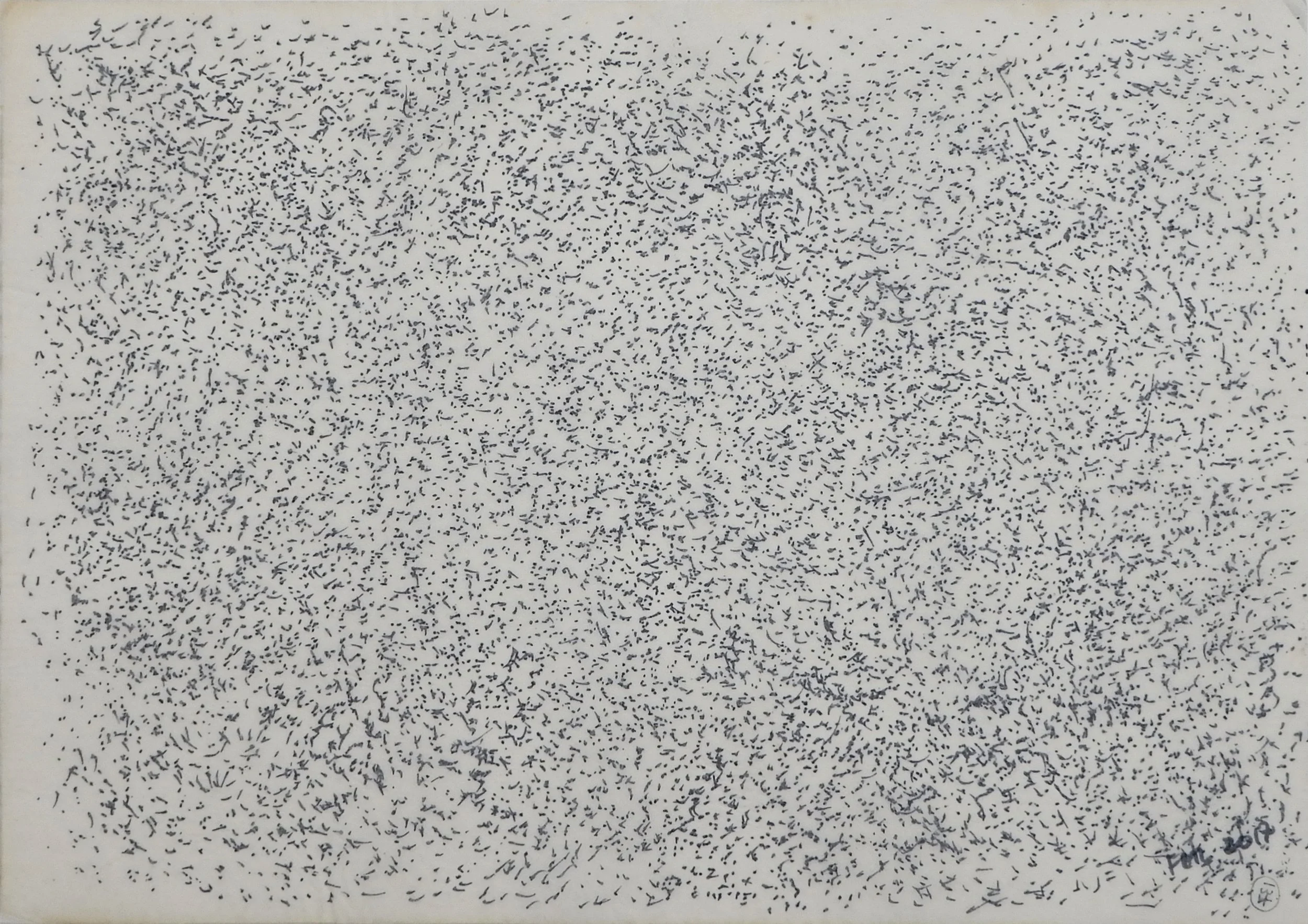

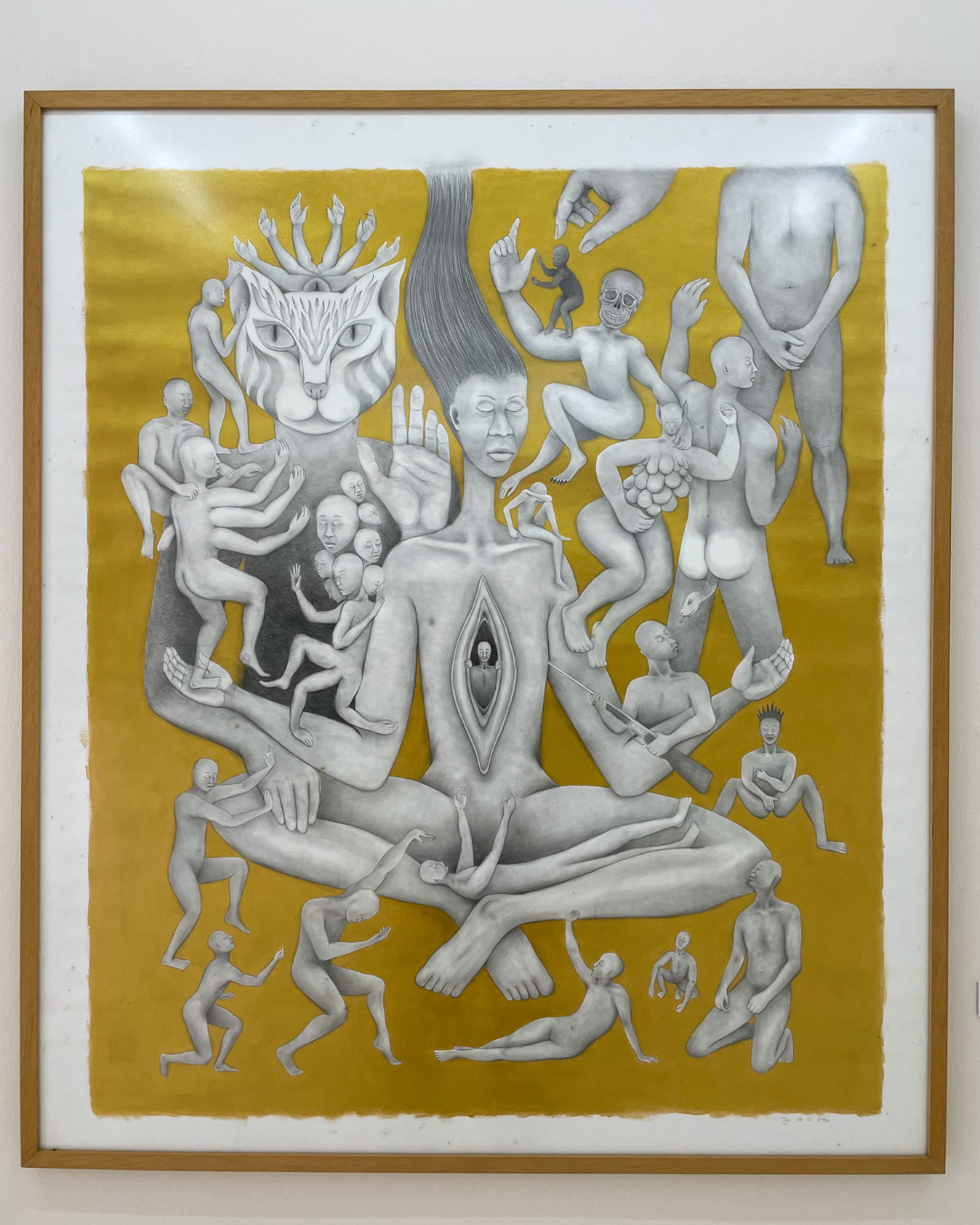

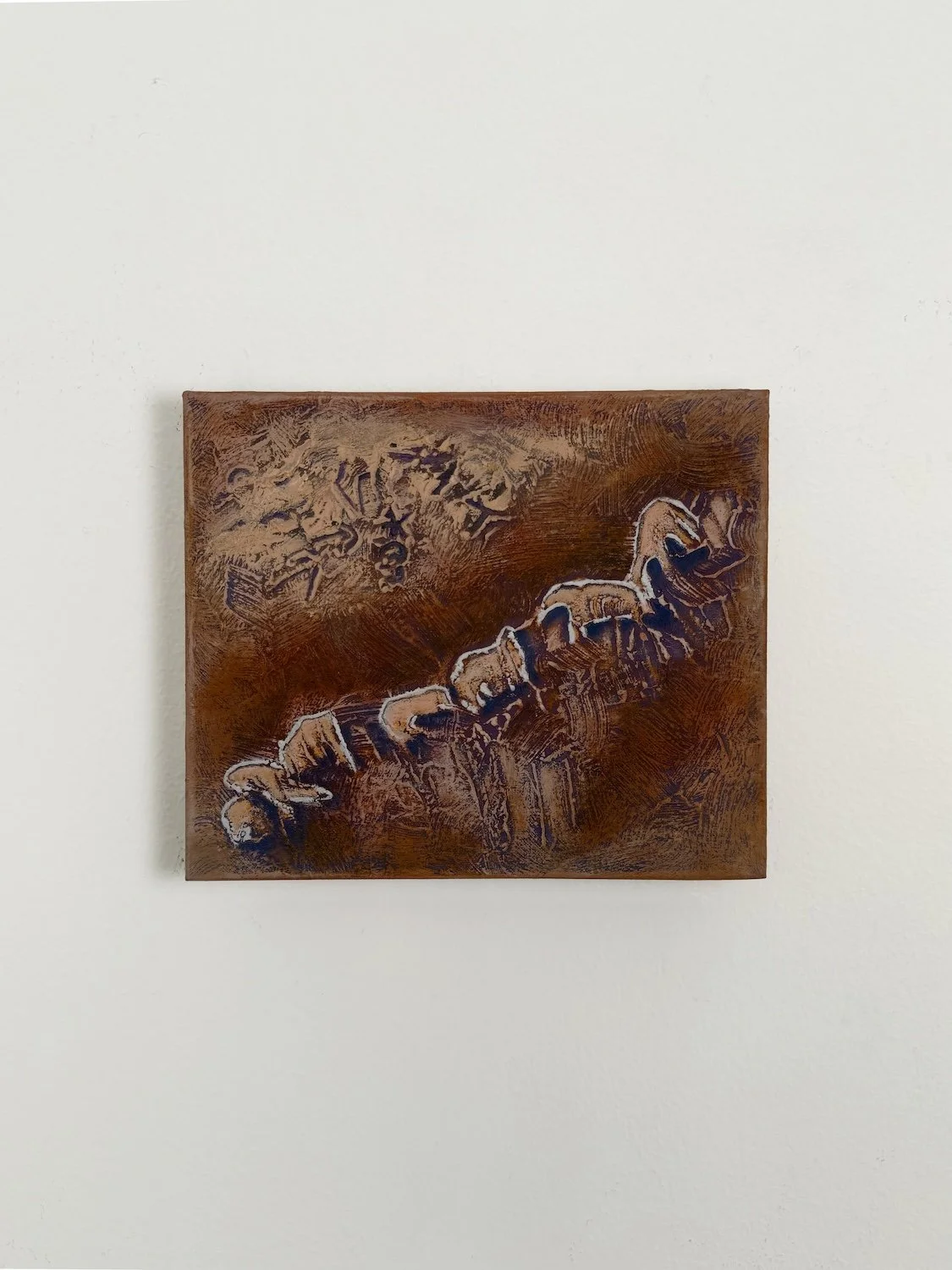

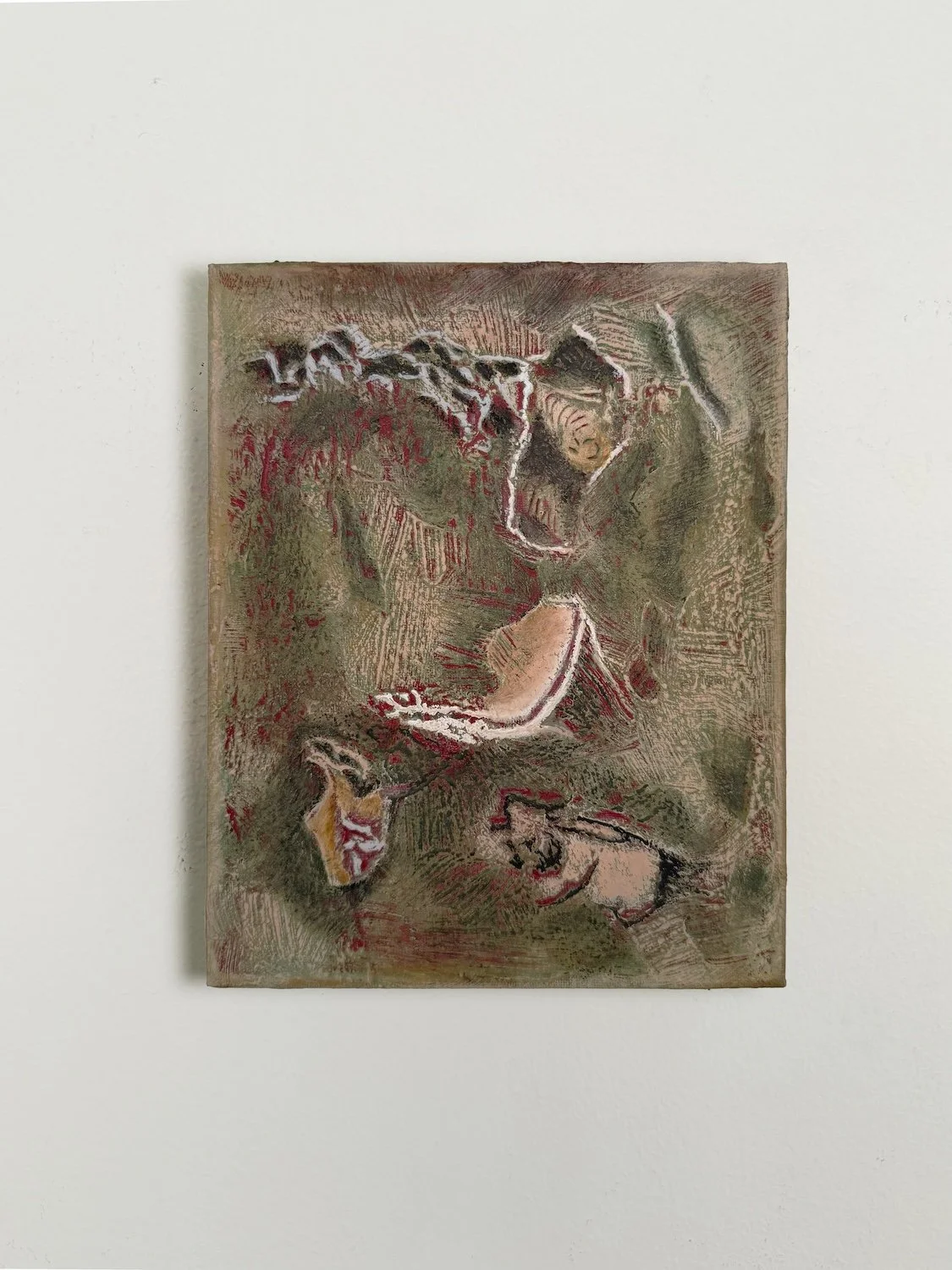

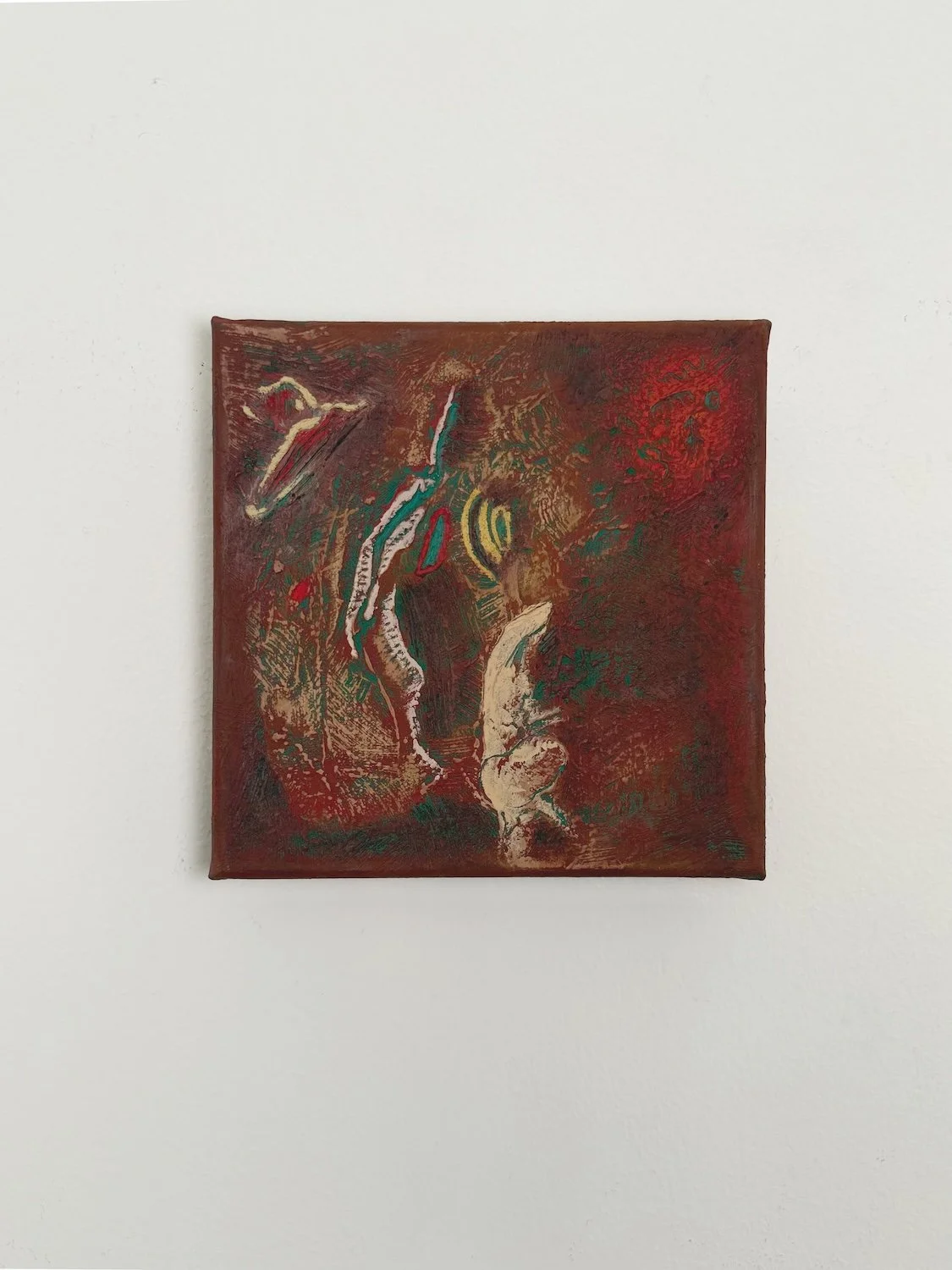

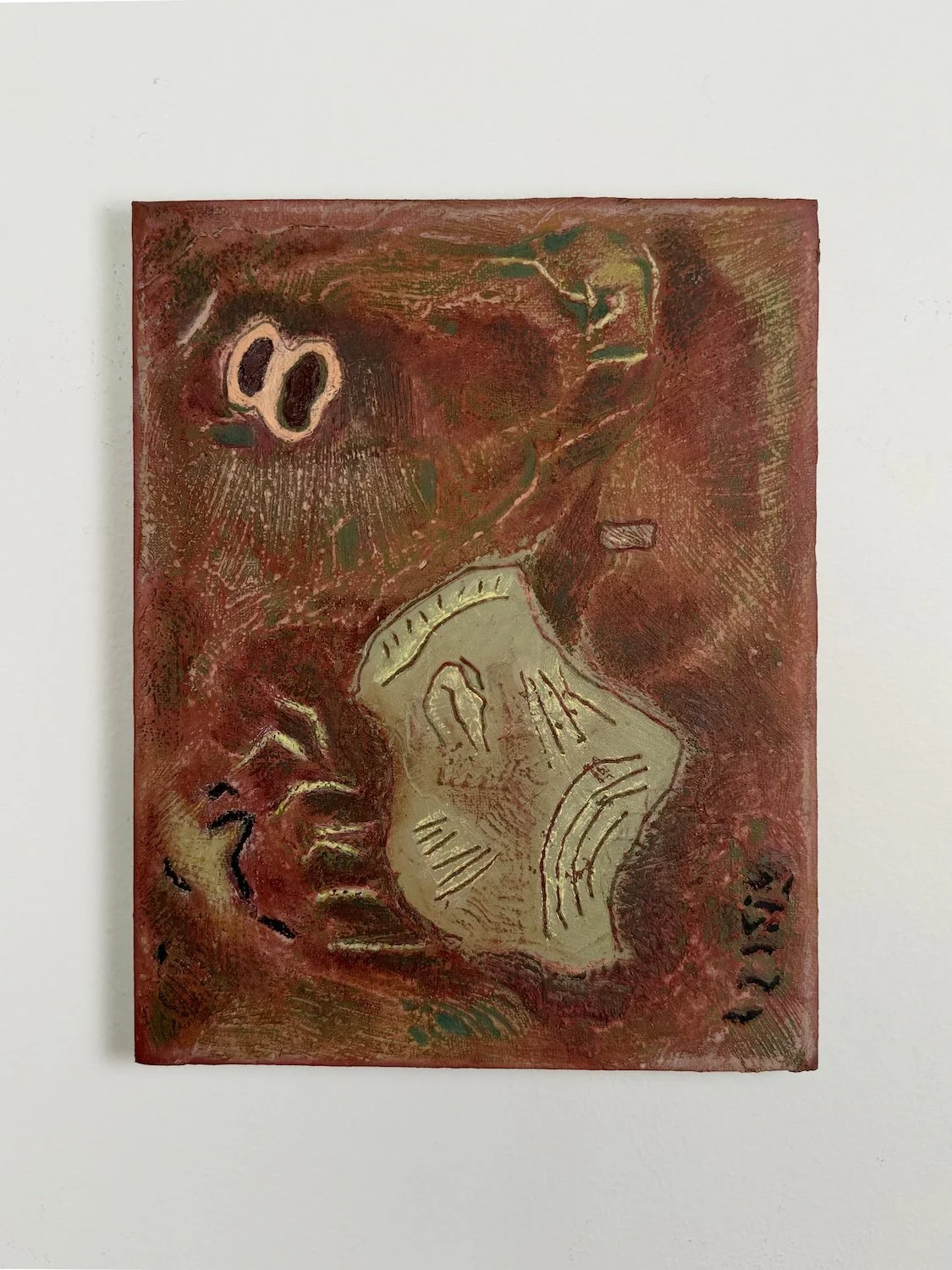

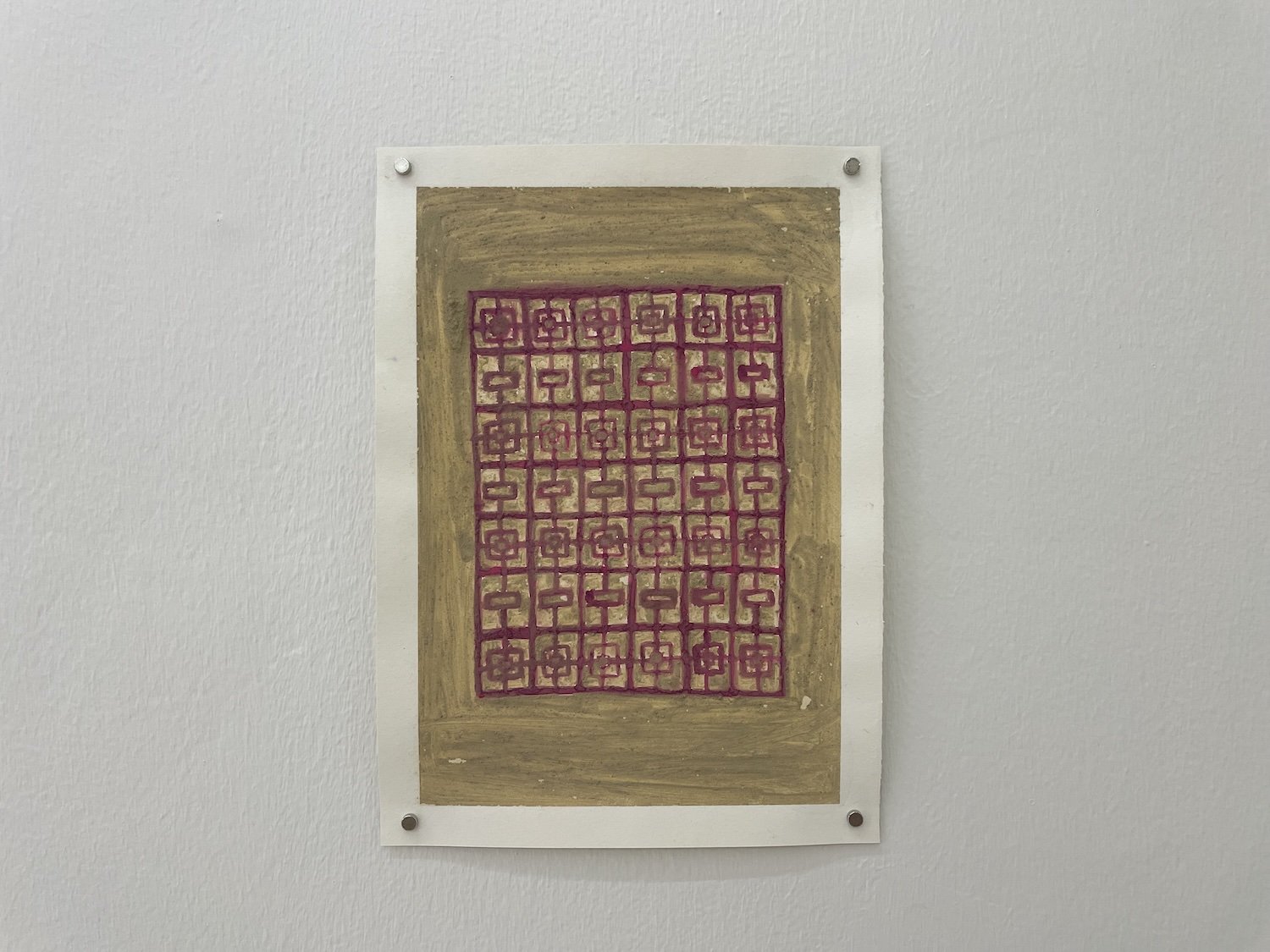

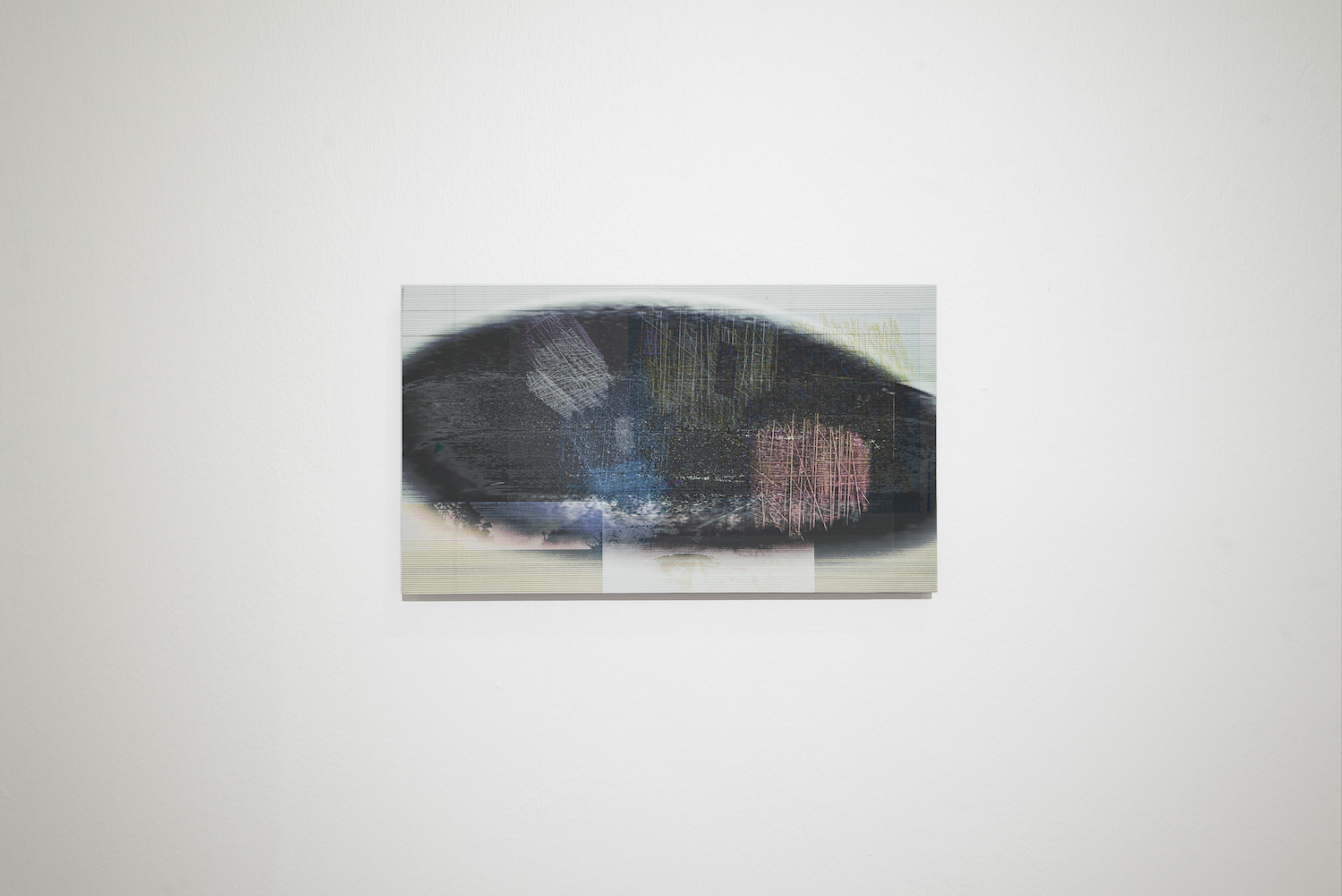

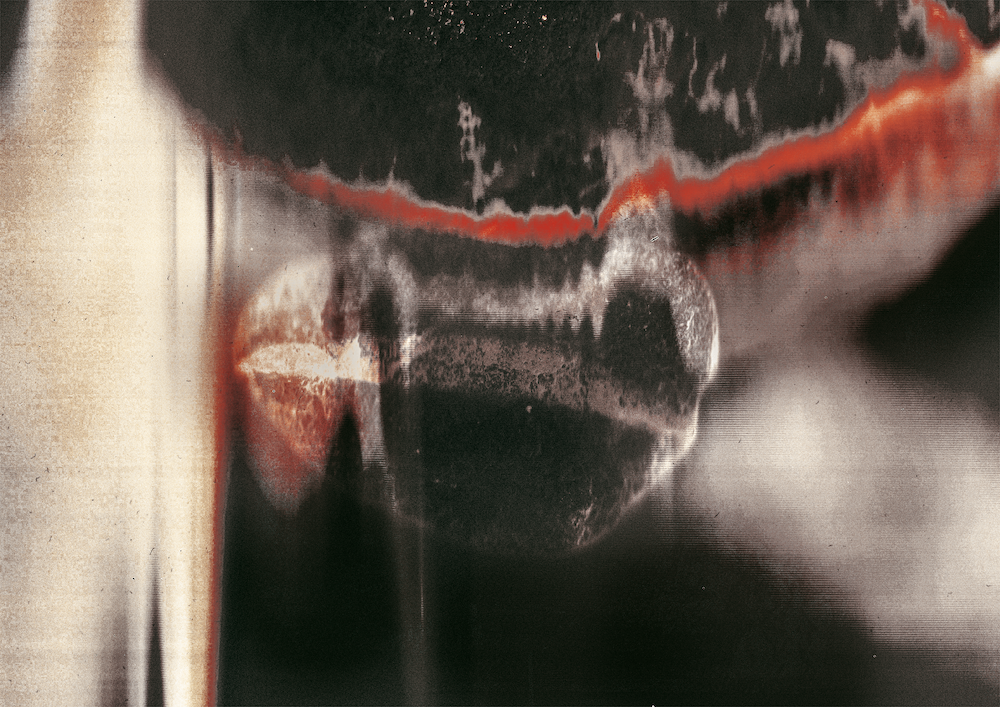

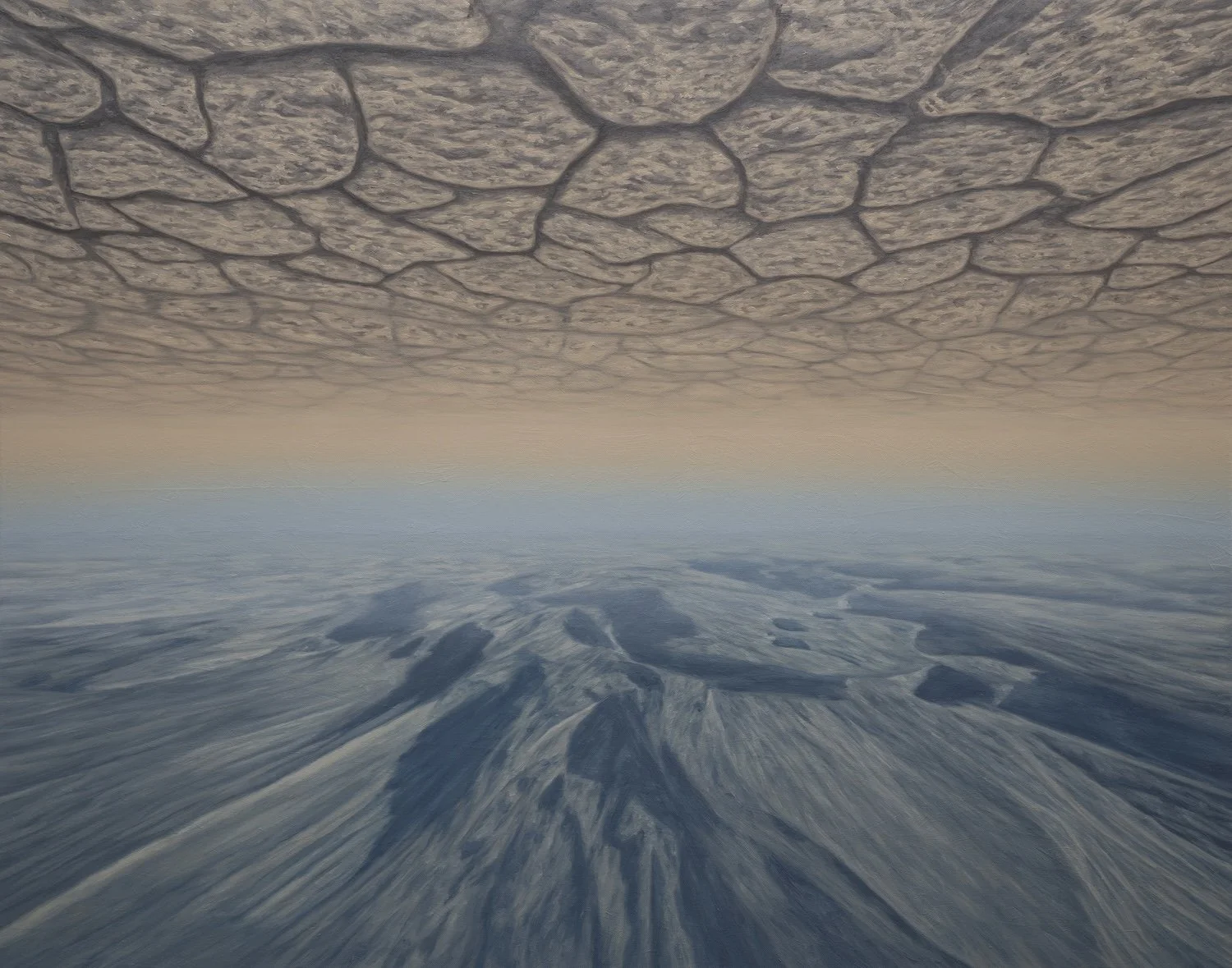

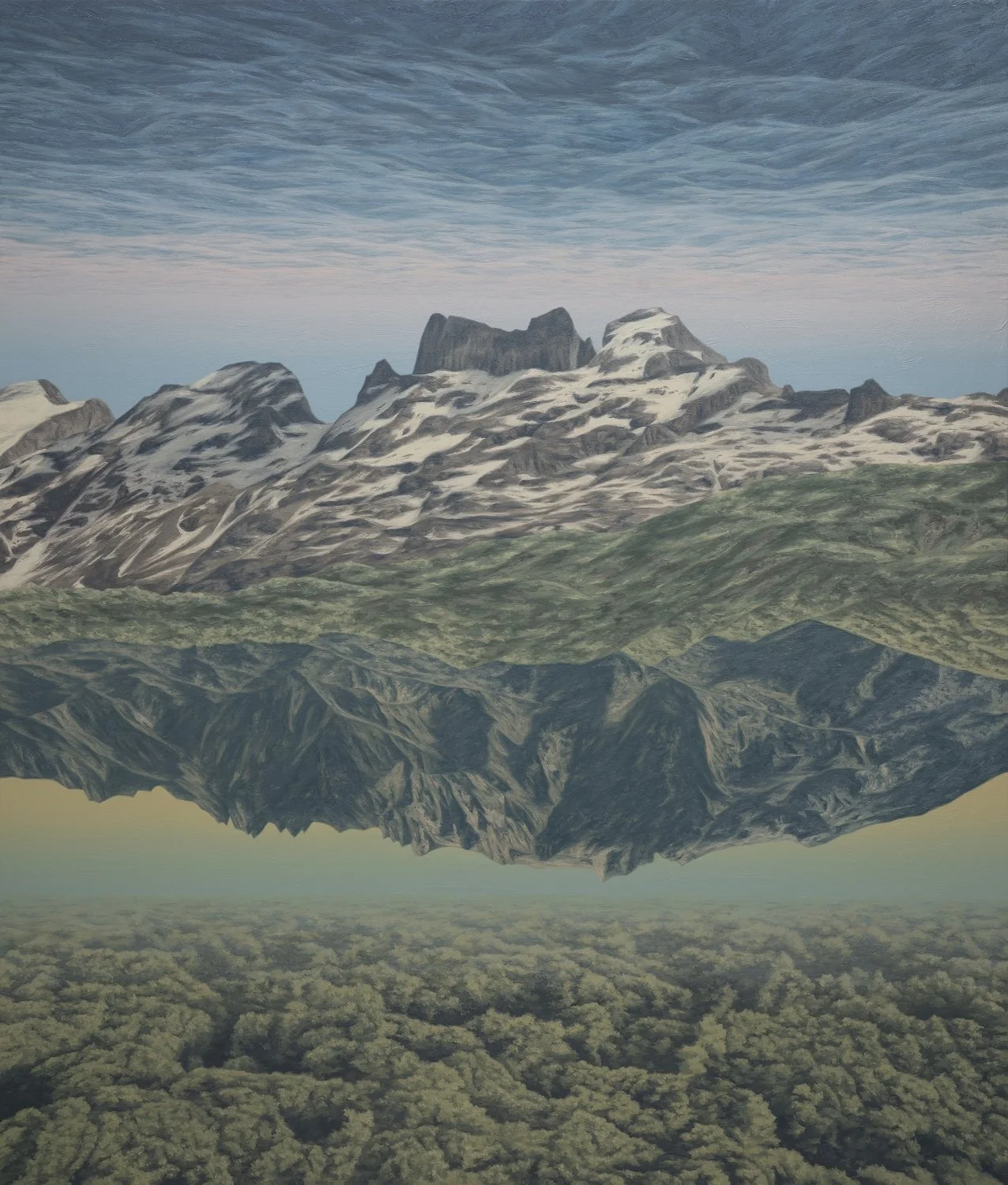

Paintings by Tong Fung Chuar and Dipali Gupta abstract the figure, turning it into swells and spirals, exploring themes of sexuality, violence, and states of liminality. Strokes by Fung threaten to swell beyond the already sizeable canvas, expressing the force of emotion, while Dipali surrenders control to the machine, using vibrators dipped in ink to make the snaky tangled figures in her shunga-inspired paintings. Their figures are indeterminate, capturing the slipperiness of identity.

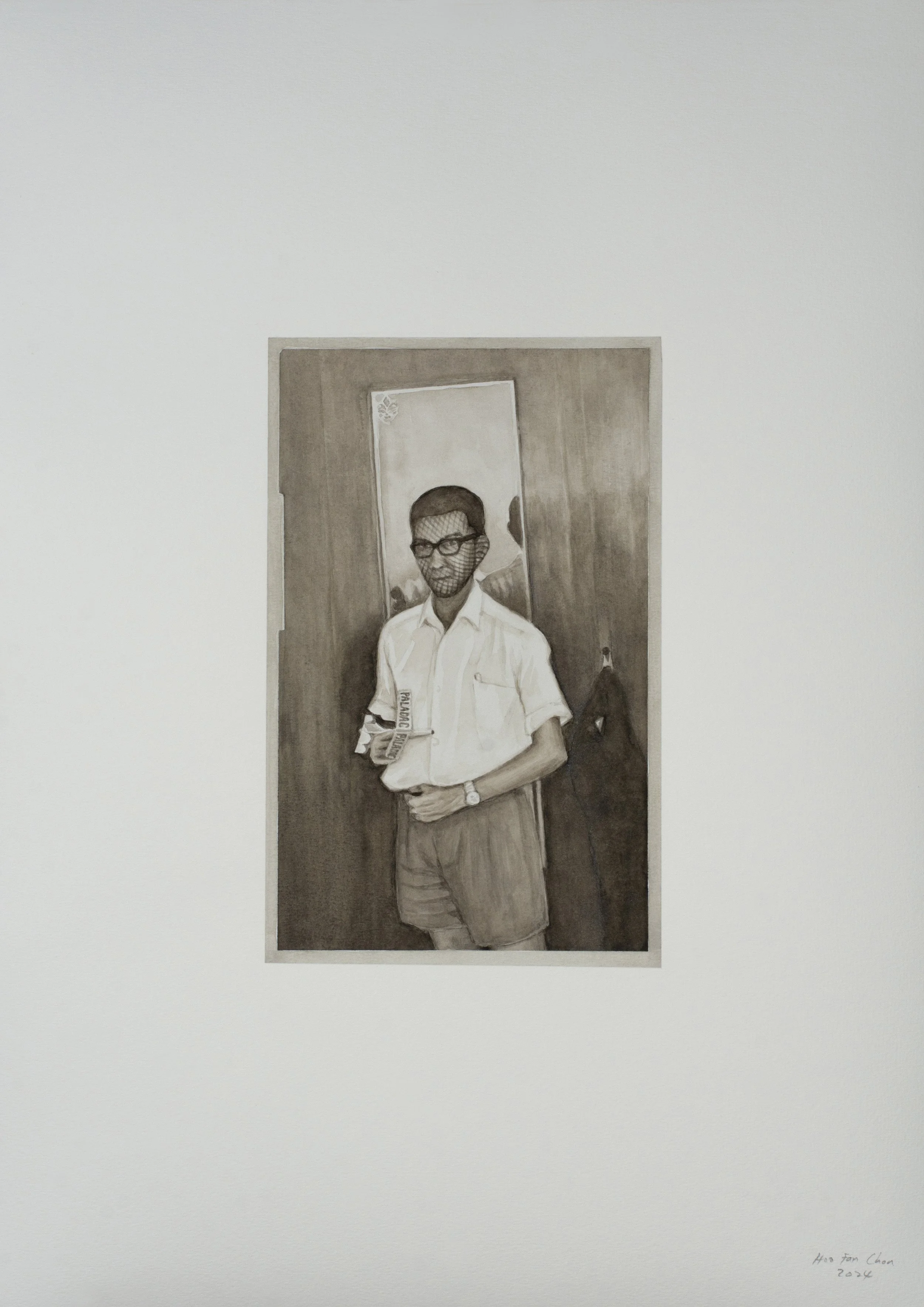

Sack Tin Lim presents the most intimate of figure paintings, a portrait of an anonymous woman stripped down to her lingerie in a setting that appears to be her room. Here, figurative painting becomes an act of voyeurism as artist and viewer are given a glimpse into the intimate world of a random subject, whose unsmiling face and closed posture reject all assumptions of familiarity.

Exhibition dates

22 November – 21 December 2025

About the Artists

Adam Badruddin Syah (b. 2000) is a young painter whose practice is inspired by the late-19th century French Impressionists but with a palette of his own artistic sensibilities. Through his choice of colours, Adam responds to the region’s unique ecology and geography, where light behaves differently from the temperate tones more familiar to Western Impressionism.

As an artist, Adam observes the lives and movements of his subjects with great curiosity and with deep joy, flipping constantly between close study of the 19th century painters he admires and curiosity for the present moment, careful to capture all the fine details. His painting spirit is encapsulated in a quote by Edgar Degas that ‘L’art n’est pas ce que vous voyez, mais ce que vous faites voir.’ (‘Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.’) This idea resonates deeply within Adam’s practice and his aim is not merely to depict, but to invite the viewer into a moment of intimacy with the subjects of his paintings.

A relatively emerging artist within the Malaysian art scene, Adam has exhibited in a handful of group exhibitions locally. Recent exhibitions include 7 Ways of Seeing (2025, CULT Gallery, KL, and Hin Bus Depot, Penang), Young, Wild & Free #2 (2024, Galeri Puteh, KL), and HOM Art Open (2023, HOM Art Trans, Selangor).

Dipali Gupta (b. 1977) is a multi-media artist whose practice explores societal constructs from the domain of the feminine. Influenced by Foucauldian biopolitics, religious habituations, socio-political constructs, and its psychosomatic effects, Dipali’s experimental works question the normative and strive to reclaim space and meaning. Her concepts usually defy myths of domestication, reproduction, spectatorship, self, and identity. Set amongst Deleuzian societies of control, her practice subverts notions of patriarchy, androcentricity and binarism. Her multi-disciplinary approach re-appropriate less significant genres by layering concepts with artistic and social canons. Her research interests include feminist theory, post humanism, the body and identity politics.

A graduate of LASALLE College of the Arts in Singapore and Goldsmith’s University in London, Gupta has accumulated accolades over the years including nominations for the Chan Davies Art Prize (2018, winner), Young Master’s Art Prize (2019), the Wells Art Contemporary Award (2020), the Sovereign Asian Art Prize (2022, finalist). Her work has been exhibited in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Kuala Lumpur, with expositions and symposiums in Portugal, London, Miami, Paris, and New Delhi. Outside of her art practice, she was the co-moderator of a reading group called Constructing the Body at Malaysia Design Archive, Kuala Lumpur, and a part-time lecturer in Cinema and Sociology at Multimedia University (MMU), Kuala Lumpur.

After several years spent in Singapore and Malaysia, Gupta is currently based in her native Mumbai. In 2025, she was a fellow at the Virginia Centre for the Creative Arts in Virginia, United States.

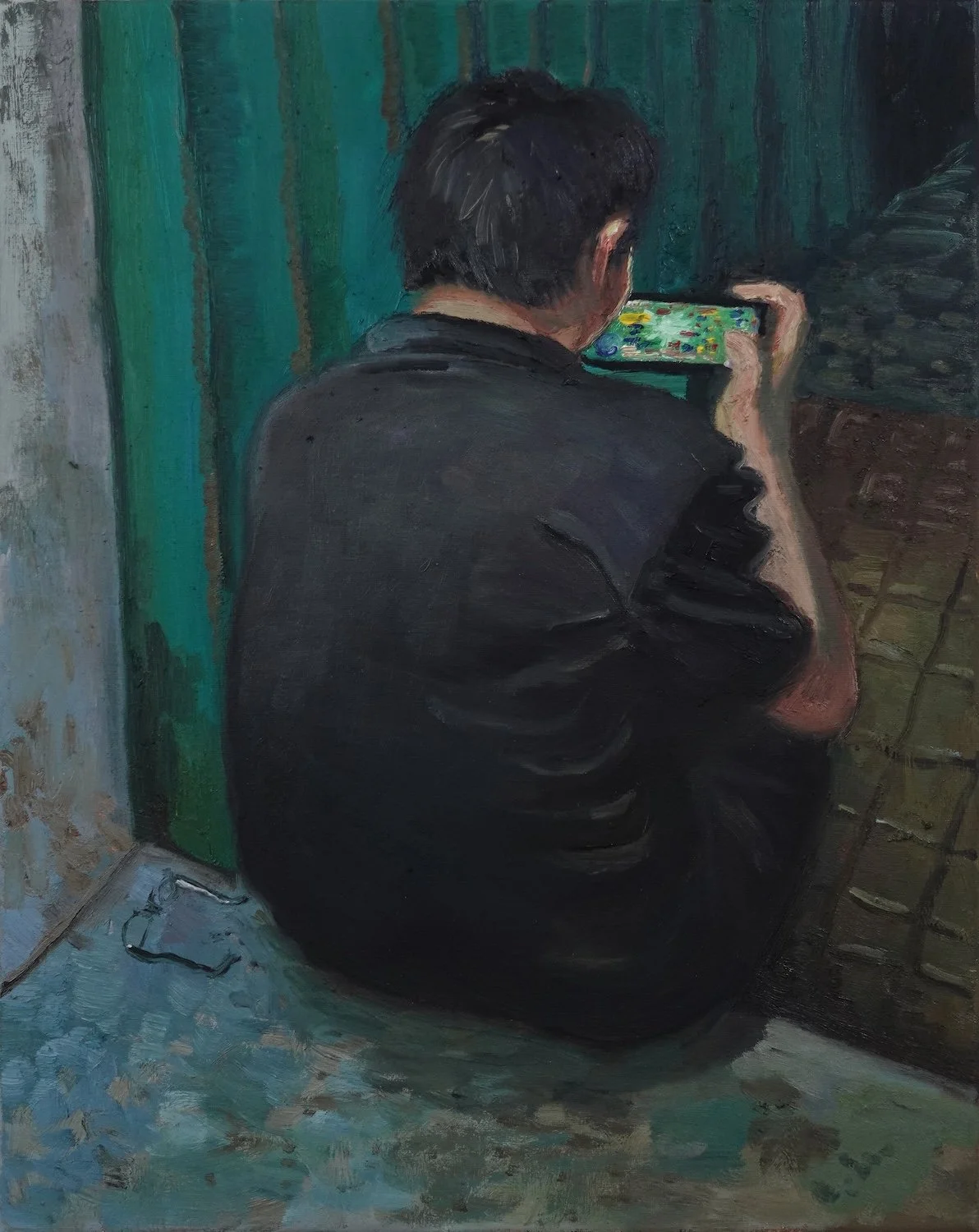

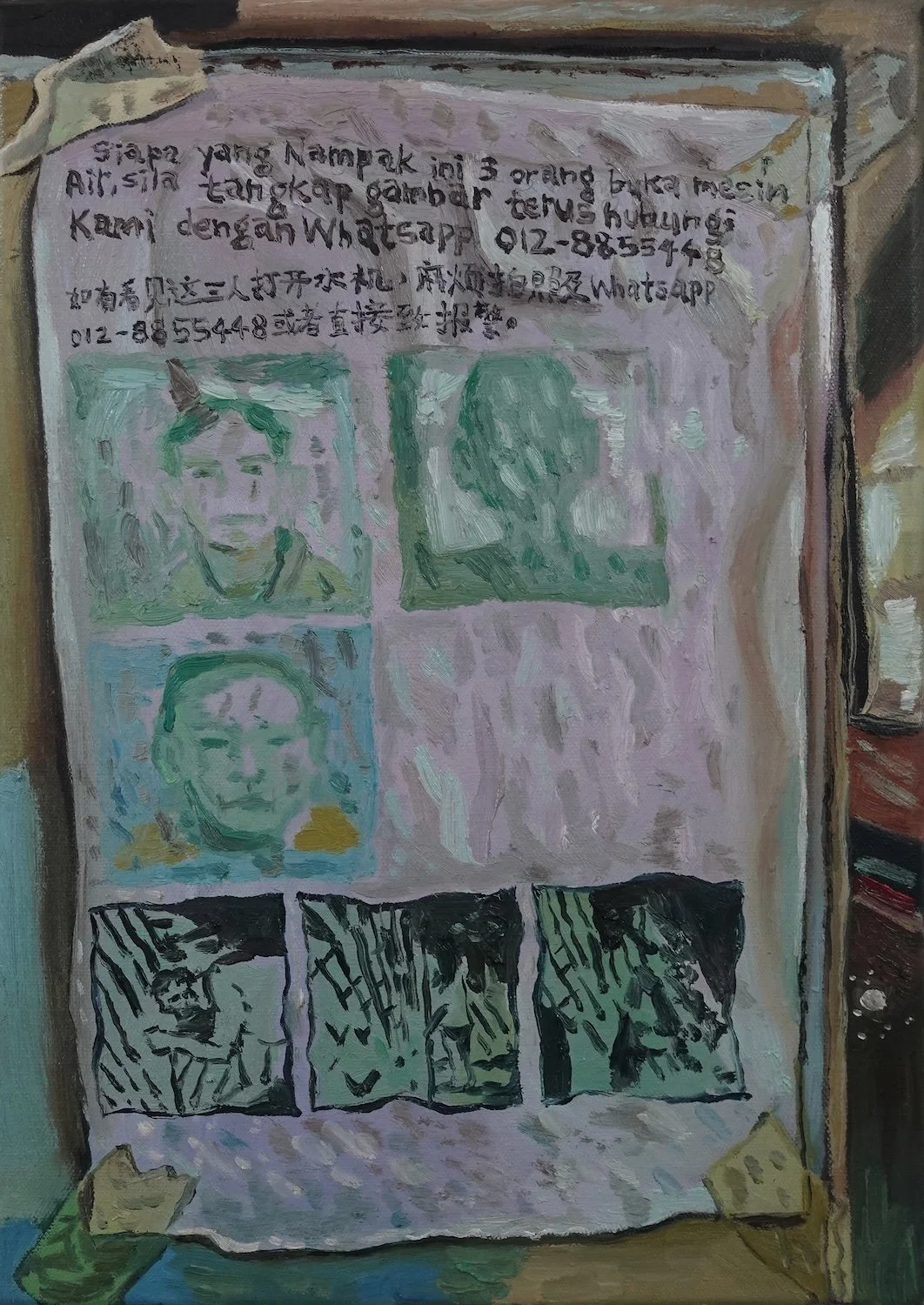

Ong Hieng Fuong (b. 1995, Selangor) is an emerging artist who is currently pursuing his Master’s in Fine Art at the printmaking department of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute in Chongqing, having previously graduated with his Bachelor’s from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Hieng hails from Tanjong Sepat, a small fishing town where the pace of life is much slower and where he got to experience all aspects of daily life to their fullest, experiences and observations that, despite his move to China, are still his core source of inspiration.

Hieng’s work has been included in group exhibitions locally and internationally, including the ILHAM Art Show 2025 (ILHAM Gallery, Kuala Lumpur), Narrating Localities (2025, University Malaysia Sabah), Art Jakarta (2024, Indonesia), and ART SG (2024, Singapore). He has been selected for the UOB Painting of the Year Award several times, winning Silver (Established) in 2025, Gold (Established) in 2019, and the Grand Prize (Emerging) in 2017. He was an artist-in-residence at the Rimbun Dahan Southeast Asian Art Residency for six months in 2021. His debut solo exhibition was That day, I was sketching on the street (2022, The Back Room, KL) and his second solo exhibition is scheduled to take place at The Back Room in February 2026.

Sack Tin Lim (b. 1990) is a painter from Sabah who is currently based in Kuala Lumpur. Sack emerged within the Malaysian art scene with his expressive portraits of individuals within Malaysia’s transgender community, the subject of his debut solo exhibition Un/Hidden Identities in 2023 (G13 Gallery, KL). His practice explores the makings and trappings of identity, and how through ornaments and appearances, individuals craft their own identity through a process not unlike that of painting.

Sack received his Bachelor of Arts in Oil Painting from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, China, and his Diploma in Illustration from The One Academy, Malaysia. Since his return to Malaysia, he has had two solo exhibitions to date: Cherry Blossom (2024, Temu House, KL) and Un/Hidden Identities: Painting Lives (2023, G13 Gallery, KL). In 2021, he was the recipient of the Silver Award (Emerging) in the annual UOB Painting of the Year Award.

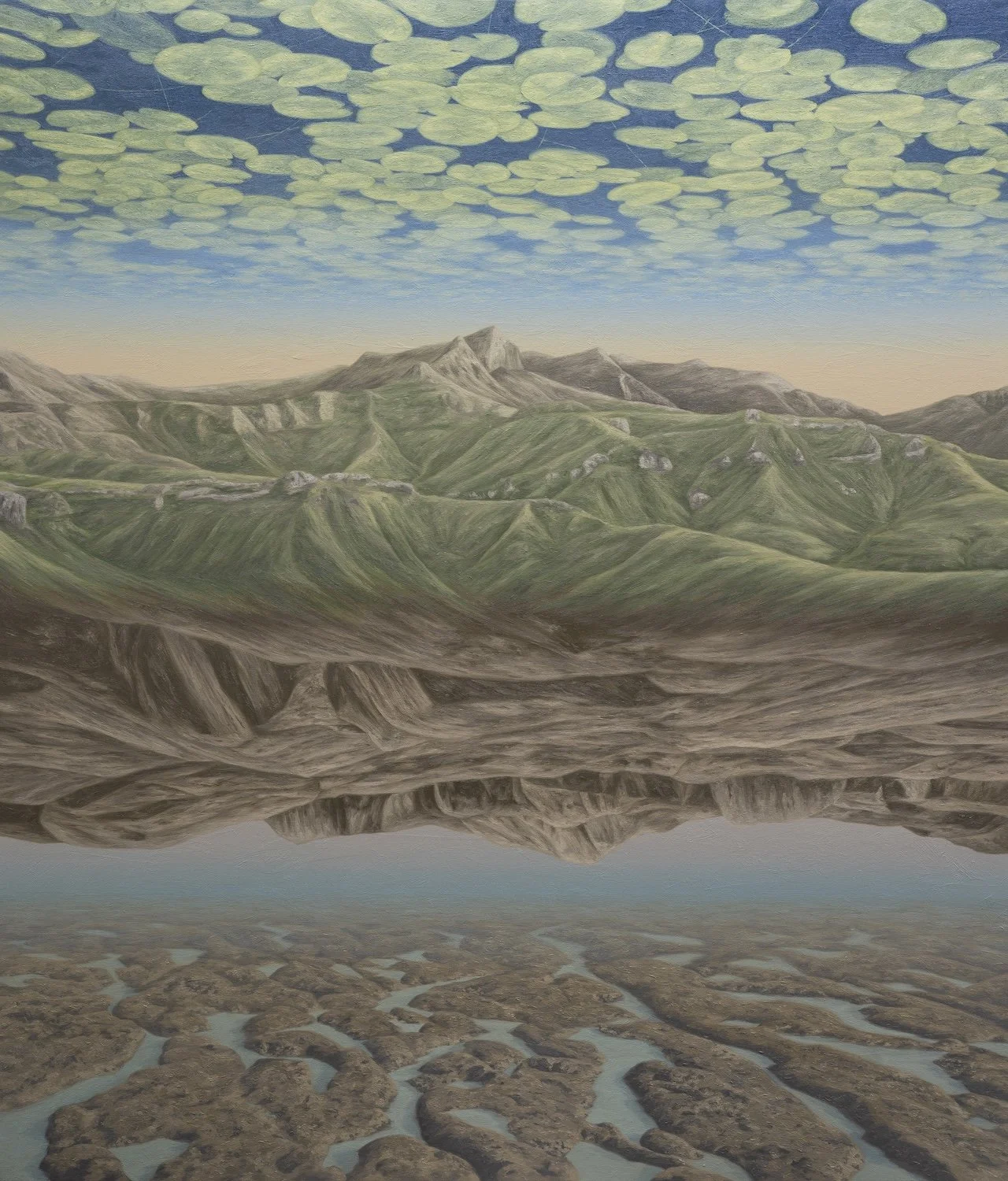

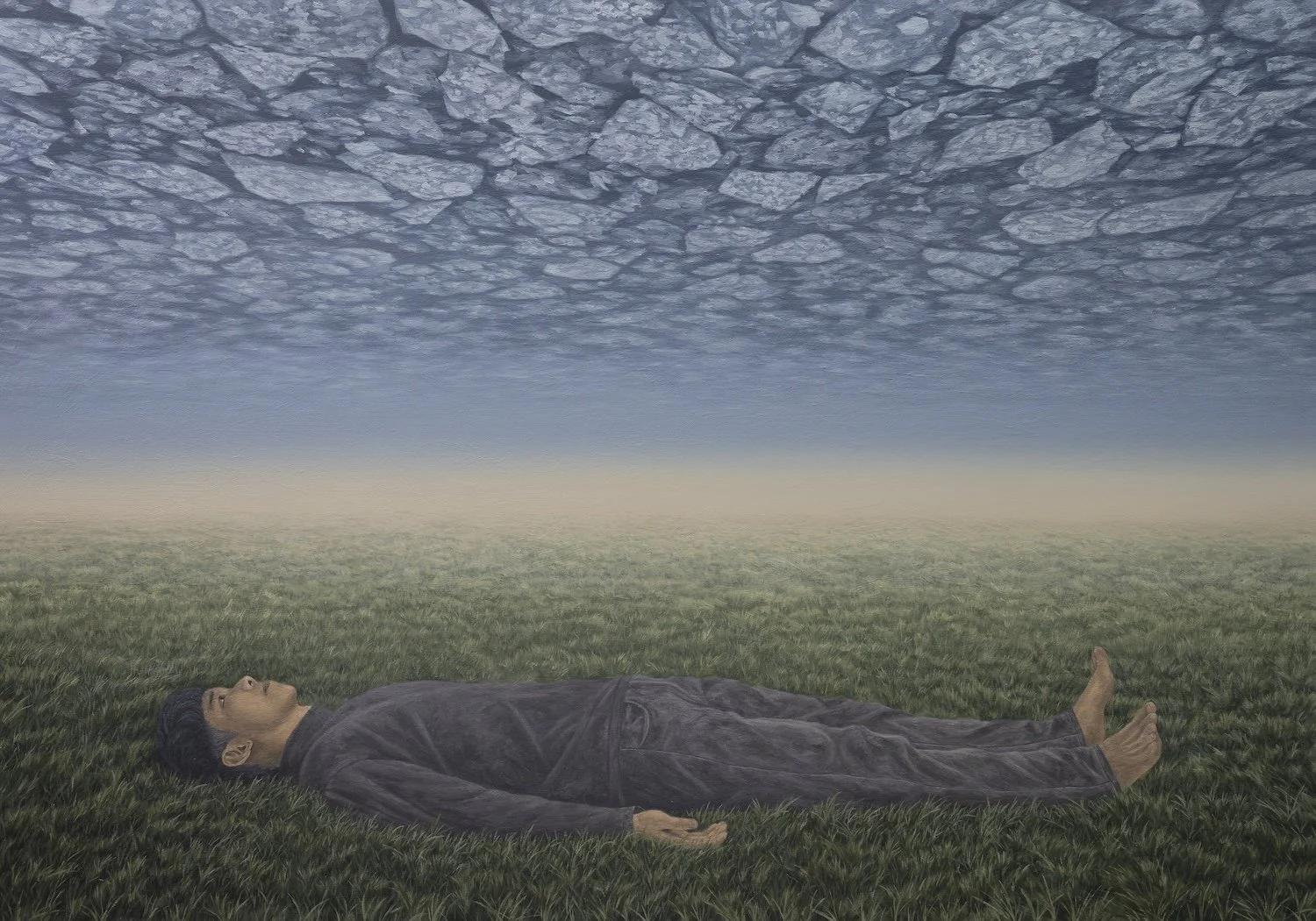

Tong Fung Chuar (b. 1996) graduated with his Master’s and Bachelor’s in Fine Art from the National School of Fine Art in Dijon, France, with a one year exchange at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China. As a painter, Tong’s themes articulate around the specific realm where corporality and senses are introduced into the imagination. The basic gestures and items are arranged to provoke a narrative, poetic absurdity in which we reflect on our relationship with objects, languages, bodies, and images.

The issues of spatial experience, animality, and violence are currently the main subjects occurring in the creation process, aimed at exploring the possibility of cohabiting these themes in a relatively harmonious situation. Tong’s debut solo exhibition was Occurs at The Zhongshan Building in 2024. He has participated in group exhibitions around Malaysia, France, and China.

Installation shots

Coming soon

Adam Badruddin Syah

Boisson du Soir

2024

Oil on corrugated board

91 × 122 cm

Framed